In today’s world, we often mix being busy with being effective. That’s where the velocity mental model comes in. Remember, just doing lots of tasks doesn’t mean we’re really getting somewhere.

This model, based on physics, helps us make better decisions and set goals. It shows the difference between just moving and actually moving in the right direction. Speed is about how fast you’re moving. But velocity asks if you’re going where you really want to go.

This subtle but profound difference explains why some people achieve remarkable results while others remain stuck despite working frantically.

The velocity mental model: Speed measures movement, velocity measures directional progress

Understanding the Velocity Mental Model

To truly grasp the velocity mental model, we need to understand its origins in physics and the various ways it applies to our daily lives and decision-making processes. This understanding can help us order our thoughts and actions, reflecting on the state of our productivity and the things that truly matter.

The Physics Behind the Mental Model

In physics, speed is a scalar quantity—it has magnitude but no direction. It simply tells you how fast something is moving. Velocity, however, is a vector quantity—it has both magnitude and direction. This distinction is crucial because two objects moving at the same speed but in different directions have different velocities.

When we translate this concept to productivity and decision-making, the implications become powerful:

Speed (Scalar)

- Measures rate of activity or “busyness” per day

- Counts emails sent, calls made, meetings attended

- Focuses on quantity of tasks completed

- Can create illusion of progress

- Often leads to burnout and frustration

Velocity (Vector)

- Measures progress toward specific objectives

- Tracks milestones achieved toward goals

- Focuses on quality and relevance of activities

- Creates actual progress and results

- Leads to satisfaction and momentum

“All too often we confuse activity with accomplishment, and this is especially prevalent in the corporate working environment.”

The Illusion of Productivity

Many of us fall into the trap of equating busyness with productivity. We pride ourselves on packed schedules and late nights at the office. But this “speed without direction” approach often leaves us exhausted and no closer to our goals, reflecting a state of confusion in our mental models.

Consider this scenario: You spend a lot of time responding to 50 emails, attending 3 meetings, and handling various small tasks. You’re moving fast, but are you moving forward?

If these activities aren’t aligned with your primary objectives, you’re demonstrating speed without velocity, missing the way to true progress.

Why Speed Alone Is Misleading

Speed might make us feel like we’re getting things done, but it’s often a trap. A study from Harvard Business Review found that 41% of knowledge workers spend most of their time on low-impact tasks. This makes us think we’re productive, but we’re not really moving forward.

Notifications, meetings, and shallow work create this illusion. The velocity mental model helps us see if our actions are really leading to results. It’s about making sure our efforts are actually making a difference.

The busyness trap: High speed doesn’t guarantee progress toward goals

The Politics of Perception

In many workplaces, being visibly busy is rewarded more than achieving actual results. This creates what Zen Tools calls “the politics of perception,” where appearing productive becomes more important than being productive.

This manifests in what they describe as “The 3 levels of wanting”:

- Wanting to do something and actually getting on and doing it (velocity)

- Wanting to be seen to be doing something (speed without direction)

- Wanting to be seen to be wanting to do something (pure perception management)

Only the first category contributes to velocity. The rest is just “busyness” that creates a “chaff screen” to deflect unwanted attention but doesn’t move the needle on important goals.

Applying the Velocity Mental Model

Understanding the velocity mental model is one thing; applying it to transform your productivity in your day-to-day tasks is another. Here’s how to put this powerful concept into practice in a way that optimizes your speed velocity and minimizes the effort required in complex systems.

Identifying Your Direction

Before you can optimize for velocity, you need clarity on your direction. This means defining your goals and priorities with precision.

Direction-Setting Questions:

- What are my top 3 priorities this quarter/month/week?

- What outcomes would make the biggest difference to my success?

- Which activities directly contribute to these outcomes?

- What am I doing that doesn’t move me toward these goals?

Once you’ve established your direction, every activity can be evaluated based on whether it moves you toward your destination or just keeps you busy.

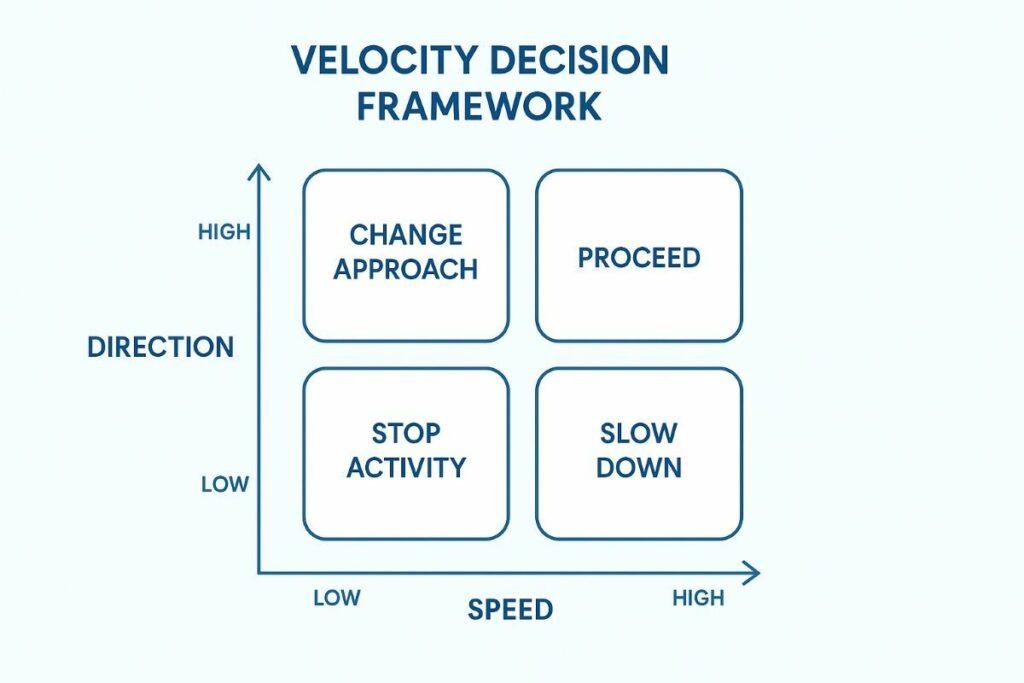

The Velocity Decision Framework

When faced with decisions about how to spend your time and energy, apply this simple framework:

The Velocity Decision Framework helps evaluate activities based on their contribution to your goals

This framework forces you to consider both the direction (alignment with goals) and the magnitude (efficiency) of your activities, which are crucial things in understanding mental models and achieving speed velocity in complex systems over time, per day, and in the long game.

Task Optimization: The Internal Locus of Control

While much advice about the velocity mental model focuses on saying “no” to external requests, there’s another crucial dimension: internal task optimization.

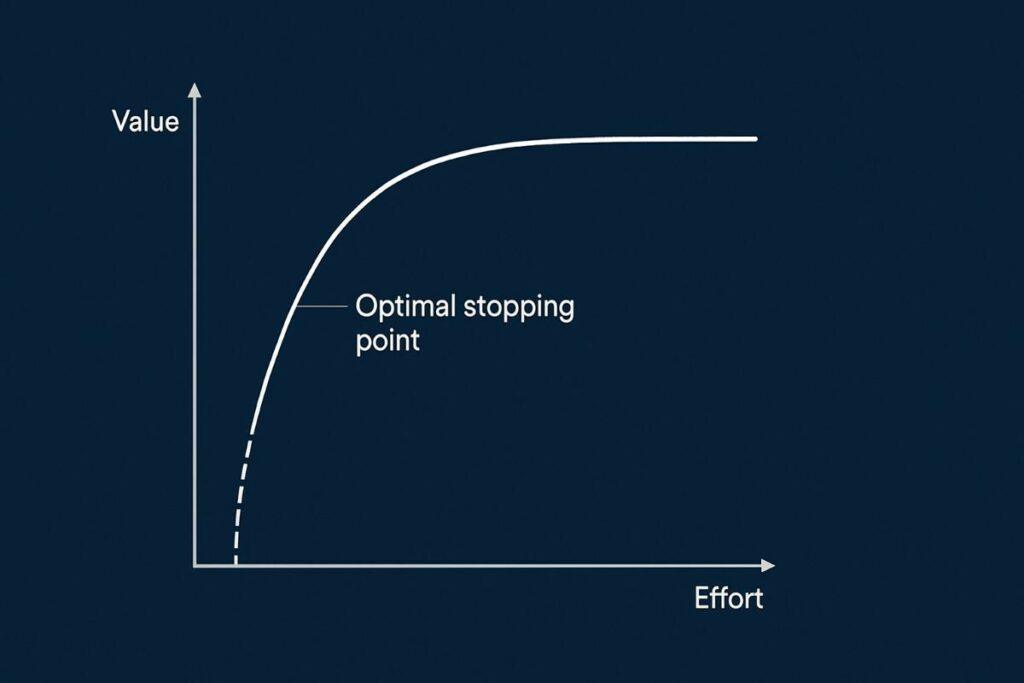

“With task optimization the locus of control is internal. This is about knowing the point at which focused ‘busyness’ does not increase velocity and starts to impede it. This is about knowing when an essential task becomes inessential.”

This requires developing the judgment to recognize when additional effort on a task yields diminishing returns. For example, spending 10 hours perfecting a presentation that would be 95% as effective after 3 hours represents poor velocity.

Ready to Apply the Velocity Mental Model?

Download our free Velocity Framework Worksheet to identify your high-velocity activities and eliminate speed-only tasks that don’t contribute to your goals.

3 Powerful Strategies to Increase Your Velocity

Now that you understand the velocity mental model, let’s explore specific strategies to help you apply it in your daily life and work.

Strategy 1: Ruthlessly Eliminate the Non-Essential

The first step to increasing velocity is removing activities that create speed without progress. This requires brutal honesty about what truly matters.

Increasing velocity starts with eliminating tasks that don’t contribute to your direction

Start by conducting a velocity audit of your calendar and to-do list:

- Review each recurring meeting and ask: “Does this directly contribute to my primary goals?”

- Examine your daily tasks and identify those that create movement but not progress

- Look for tasks you can delegate, automate, or eliminate entirely

- Consider the “opportunity cost” of each activity—what high-velocity work could you do instead?

Remember that saying “no” to low-velocity activities isn’t selfish—it’s strategic. It allows you to say “yes” to the work that truly matters.

Strategy 2: Create Systems, Not Willpower

Relying on willpower to maintain velocity is a losing strategy. Instead, design systems that naturally channel your energy toward high-velocity activities.

Willpower-Based Approach

- Constantly deciding what to prioritize

- Fighting distractions as they arise

- Making case-by-case decisions about requests

- Depletes mental energy quickly

- Fails under stress or fatigue

Systems-Based Approach

- Pre-determined priorities and boundaries

- Environmental design that minimizes distractions

- Default responses for common requests

- Preserves mental energy for important work

- Remains effective even under pressure

Effective velocity-enhancing systems might include:

- Time blocking: Designate specific hours for high-velocity work when you’re at your best

- Communication protocols: Set expectations about email response times and availability

- Decision rules: Create simple if-then guidelines for common scenarios

- Environment design: Structure your physical and digital workspace to minimize distractions

- Batch processing: Group similar low-velocity tasks to handle efficiently

One particularly effective system is the “no meeting mornings” rule. By protecting your peak cognitive hours for high-velocity work, you ensure that your best energy goes toward your most important goals.

Strategy 3: Master the Art of Strategic “No”

Perhaps the most challenging but crucial velocity-enhancing skill is learning to say “no”—even to your boss or important stakeholders.

Strategic “no” involves redirecting conversations toward priorities and trade-offs

The key is framing your “no” not as a refusal but as a prioritization discussion:

Instead of saying: “I can’t take on that project.”

Try: “I’d be happy to help with this. Given my current priorities on X, Y, and Z, how would you like me to reprioritize?”

Instead of saying: “That’s not my job.”

Try: “I notice this falls outside my core responsibilities where I can add the most value. Would it make sense to involve someone from team X who specializes in this?”

Instead of saying: “I don’t have time.”

Try: “I want to make sure I can deliver quality work. Given my current commitments, I could start on this in two weeks. Would that timeline work, or should we explore alternatives?”

This approach acknowledges the request while initiating a conversation about priorities and trade-offs. It demonstrates your commitment to high-velocity work rather than simply refusing tasks.

Case Study: From Busy to Productive with the Velocity Mental Model

To illustrate the power of the velocity mental model in action, let’s examine a real-world example drawn from the Zen Tools article.

The Content Creation Velocity Challenge

The author of the Zen Tools article described their experience creating daily content for their website. They identified three main tasks in their content creation process:

- Reading and researching subject material

- Drafting and formatting the material

- Posting the material as a webpage

Through experience, they discovered that steps 2 and 3 consistently required about 2-3 hours. However, step 1—research—could expand indefinitely if not carefully managed.

One morning, while researching the speed and velocity topic, they found themselves “getting drawn deeper and deeper into the physics of this subject,” which they found “interesting and challenging” but ultimately recognized was beyond the scope of their article.

This is where the velocity mental model proved invaluable. They realized they had reached “the optimum allocation of resource and effort that was required” for the research phase. Continuing would create more speed (more research activity) but not more velocity (progress toward publishing the article).

By recognizing when an essential task (research) was becoming non-essential (excessive detail beyond the article’s scope), they maintained their velocity and successfully published their daily content.

Key Lessons from the Case Study

This example highlights several important aspects of applying the velocity mental model:

- Task optimization requires experience: The author mentioned they could make this call because of “extensive experience of this process”

- Clear criteria are essential: They had “an established set of criteria” for determining when enough research was enough

- Internal locus of control: The decision wasn’t about external factors but about their own judgment of diminishing returns

- Perfectionism kills velocity: Recognizing when “good enough” serves the goal better than “perfect”

Task optimization involves recognizing the point of diminishing returns

This case study demonstrates that applying the velocity mental model isn’t just about saying “no” to others—it’s also about knowing when to say “enough” to yourself.

Overcoming Common Obstacles to Velocity Thinking

Despite its power, implementing the velocity mental model isn’t always straightforward. Here are some common obstacles and how to overcome them.

The Culture of Busyness

Many organizations reward visible busyness over actual results. This cultural pressure can make it difficult to focus on velocity over speed.

How to Navigate the Busyness Culture

- Document and communicate your results, not just your activities

- Find allies who understand and value velocity-based work

- Educate others about the difference between activity and accomplishment

- Demonstrate the superior outcomes of velocity-focused approaches

Pitfalls to Avoid

- Don’t get drawn into “performative busyness” to fit in

- Avoid judging your productivity by hours worked

- Don’t mistake urgency for importance

- Beware of the trap of competing on who’s busiest

Fear of Missing Out (FOMO)

The worry that saying “no” might mean missing important opportunities can undermine velocity thinking.

Remember that every “yes” to a low-velocity activity is a “no” to something with higher velocity. The real question isn’t what you might miss by saying no, but what you’re definitely missing by saying yes to the wrong things.

Unclear Direction

Without a clear sense of direction, it’s impossible to distinguish between speed and velocity. If you’re struggling to apply the velocity mental model, you might need greater clarity on your goals.

Without clear direction, it’s impossible to distinguish between speed and velocity

Take time to define your north star—the clear objective that allows you to evaluate whether your movement constitutes progress.

The Urgent vs. Important Trap

Often, urgent matters demand speed while important matters require velocity. Learning to distinguish between these and prioritize accordingly is essential for velocity thinking.

| Category | Characteristics | Examples | Approach |

| Urgent & Important | Crises, pressing problems, deadline-driven projects | Client emergency, system outage, imminent deadline | Handle immediately but analyze how to prevent in future |

| Not Urgent but Important | High-velocity activities that drive long-term success | Strategic planning, relationship building, skill development | Schedule dedicated time and protect it rigorously |

| Urgent but Not Important | Interruptions, some meetings, many requests | Most emails, many phone calls, impromptu meetings | Delegate, defer, or decline when possible |

| Neither Urgent nor Important | Distractions, time-wasters, trivial tasks | Excessive social media, office gossip, busywork | Eliminate ruthlessly |

The highest velocity work often falls in the “important but not urgent” quadrant—the very category most likely to be sacrificed when we focus on speed over velocity.

Measuring Your Velocity: Metrics That Matter

To improve your velocity, you need ways to measure it. Here are some approaches to tracking your progress.

Outcome-Based Metrics

Rather than tracking activities (speed), focus on outcomes (velocity):

- Project milestones completed vs. hours worked

- Key results achieved vs. tasks checked off

- Impact generated vs. effort expended

- Progress toward goals vs. busyness level

The Weekly Velocity Review

Implement a simple weekly review to assess and improve your velocity:

A weekly velocity review helps identify high-velocity activities and eliminate speed traps

This simple practice helps you continuously refine your understanding of what constitutes high-velocity work in your specific context.

The Velocity Ratio

Consider tracking your “velocity ratio”—the percentage of your time spent on activities that directly contribute to your primary goals versus those that don’t.

A high velocity ratio doesn’t necessarily mean working more hours—it means ensuring that the hours you work are aligned with your direction.

How to Audit Your Weekly Velocity

A weekly velocity audit helps you see where your time goes. It shows if it aligns with your goals. Start by tracking time for your top three goals.

Then, compare it to time on reactive tasks, interruptions, and admin. Use tools like time-tracking apps or calendar heatmaps for insights. Aim to spend more time on high-velocity work and less on busywork.

Master the Art of Velocity Thinking

Download our comprehensive Velocity Thinking Toolkit with templates, exercises, and strategies to help you maximize progress toward your most important goals.

Get Your Free Velocity TemplateConclusion: Prioritize the Velocity Mental Model for Meaningful Progress

The velocity mental model is more than a quick fix. It’s a way to make better choices and reach your goals. In today’s fast-paced world, it teaches us to focus on direction, not just speed. It tells us to measure what matters, not just how hard we work.

To use this model well:

Focus on the results, not just the tasks.

Get rid of work that doesn’t move you forward.

Create systems that help you make quick, smart choices.

Check your progress every week.

Learn to say “no” to things that distract you and “yes” to what’s important.

If you’re drowning in tasks, remember: rushing in the wrong direction just makes you more lost. Choosing velocity over speed is not just wise—it’s life-changing.

In a world that celebrates speed, choosing velocity is a radical act. It means prioritizing progress over motion, results over activity, and impact over optics.

Velocity thinking leads to meaningful achievements, not just busy days

Start applying the velocity mental model today and understand the activation energy mental model. Identify your direction, eliminate the non-essential things, create supporting systems, and learn to say “no” strategically. The best way to ensure you’re making progress is to focus on what truly matters. Your future self will thank you for the progress you’ve made, not just the motion people have generated.

Key Takeaways

- Speed is how fast you’re moving; velocity is how fast you’re moving toward your goals

- The velocity mental model helps distinguish between activity and accomplishment

- Increasing velocity requires clarity of direction and ruthless elimination of the non-essential

- Systems are more effective than willpower for maintaining high velocity

- Learning to say “no” strategically is essential for protecting high-velocity work

- Task optimization involves recognizing when continued effort yields diminishing returns

- Measure outcomes and progress, not just activity and effort