Ever judged something quickly because it “felt familiar”? That instant feeling is due to the representativeness heuristic mental model. Nobel Prize winner Daniel Kahneman first looked into this.

It’s how we quickly judge people, risks, and situations by looking for patterns, not always using real data.

First described by psychologists Amos Tversky and Daniel Kahneman in 1974, the explains how we compare new situations to existing stereotypes. For example, you might assume someone is a librarian rather than a salesperson just because they wear glasses and carry books—even if statistics suggest otherwise.

Why does this happen? Our brains crave efficiency. Instead of analyzing complex data, we lean on quick comparisons. But these shortcuts can lead to flawed decisions—from financial choices to hiring practices.

The good news? Awareness gives you power to pause and ask: “Am I relying on similarity or reality?”

Key Takeaways

- The representativeness heuristic mental model helps us make fast decisions by comparing situations to familiar patterns

- It often ignores statistical probabilities in favor of surface-level similarities

- Everyone uses it daily, from professionals making business calls to shoppers choosing products

- Recognizing this habit is the first step toward more objective choices

- Practical examples in later sections will show how to spot and adjust this thinking

By understanding the representativeness heuristic, you’ll start seeing these hidden influences in everyday decisions. Let’s explore how to turn this knowledge into wiser choices.

Intro to Cognitive Biases and Heuristics

Imagine walking through a grocery store—you grab familiar brands without reading labels. Your brain does this with decisions too, using invisible shortcuts, or heuristics, to save energy. These quick pathways shape how we interpret the world, often influenced by representativeness and bias, for better or worse.

Why We Need Mental Speed Bumps

Every day, people make about 35,000 choices. Our minds developed heuristics—simple rules from past experiences—to handle this load. Think of them like kitchen shortcuts: useful for daily tasks but risky when baking a wedding cake.

When Helpful Habits Become Hidden Traps

While these shortcuts save time, they can twist reality. A nurse might misdiagnose a patient by focusing on obvious symptoms. An investor could overlook data favoring a “gut feeling.” These biases act like optical illusions for our thinking.

Here’s what matters most:

• Helpful heuristics speed up routine choices

• Harmful biases distort complex decisions

• Both operate beneath our awareness

Even brilliant minds get tricked. Studies show 90% of drivers believe they’re above-average—a clear thinking error. The key isn’t eliminating heuristics, but recognizing when they override evidence.

Want to spot these patterns? Start noticing when you feel certain without checking facts. That moment of confidence might be a shortcut bypassing better decisions.

The Representativeness Heuristic Mental Model Explained

Why do penguins confuse us as birds while eagles feel instantly recognizable? This puzzle reveals how our brains categorize reality. We judge what’s probable by comparing things to ideal examples we’ve stored—not by crunching numbers.

Definition and Key Concepts

The representativeness mental model works like a sorting machine. When meeting someone quiet who loves books, you might label them a librarian—not a salesperson—because they match your perfect example of that role. Actual statistics about job numbers get ignored.

Your mind creates prototypes: gold standards for categories. Robins represent “birdness” better than ostriches. Doctors in TV scrubs feel more authentic than those in jeans. These templates help us decide quickly—but often inaccurately.

Three critical gaps emerge:

- Mistaking similarity for probability

- Overlooking how rare some categories truly are

- Assuming typical traits guarantee group membership

A startup founder might seem “unlikely to succeed” if they don’t match the Zuckerberg mold. Yet innovation often comes from unexpected places. Your brain’s need for pattern-matching can blind you to statistical truths.

When have you confused “looks right” with “is right”? That moment holds the key to smarter choices.

How the Representativeness Heuristic Skews Perception in Modern Life

We all use the representativeness heuristic in our daily lives. It’s not just in labs or theory. We make mistakes by judging based on how things look, not on facts. This can change the results of our decisions.

In a 2018 study, people who looked like they belonged in a job were 41% more likely to get it. Even if their skills were not as strong. Doctors also judged male patients with heart symptoms as riskier than female patients with the same symptoms. These examples show how our brains tend to match patterns instead of focusing on details.

Being aware is the first step. Then, we need to train our minds. We should learn to pause, ask for specific data, and not jump to conclusions.

Historical Context and Origins

How did a 2,400-year-old debate about chairs and trees shape modern decision science? Ancient Greek philosophers first wrestled with how humans sort the world into categories—a puzzle that still influences psychology today.

The Pioneering Work by Kahneman and Tversky

In 1974, Daniel Kahneman and Amos Tversky uncovered a pattern: people often ignore statistics when making guesses. Their research showed we judge likelihoods by comparing things to ideal examples—like assuming quiet book lovers must be librarians. This work earned Kahneman a Nobel Prize, proving even experts fall for cognitive shortcuts.

Evolution of Thought from Plato to Modern Prototype Theory

Plato argued every object has an essential definition. His student Aristotle created 10 category buckets for all knowledge. But psychologist Eleanor Rosch changed the game in the 1970s. Her prototype theory explained why robins feel more “bird-like” than penguins—we classify based on typical traits, not strict rules.

| Thinker | Contribution | Impact |

|---|---|---|

| Plato (4th c. BCE) | Theory of ideal forms | Founded categorization logic |

| Aristotle (384-322 BCE) | 10 universal categories | Systematized knowledge |

| Eleanor Rosch (1970s) | Prototype theory | Explained fuzzy boundaries |

| Kahneman & Tversky (1974) | Representativeness heuristic | Revealed decision-making flaws |

This intellectual journey shows how ancient questions about chairs (“What makes a chair a chair?”) evolved into tools for better business choices and fairer hiring. When have you confused a good story with solid evidence? That’s history shaping your thinking.

Real Life Examples and Case Studies

Picture this: A coin lands heads-tails-heads-tails. Does this pattern feel more “random” than six heads in a row? Your answer reveals how we confuse storytelling with statistics. Let’s examine two landmark experiments that expose this universal thinking quirk.

Linda and Steve: When Stories Beat Math

Researchers described Linda as a philosophy major who protested injustice. When asked if she’s more likely to be a bank teller or a feminist bank teller, 85% chose the second option. But here’s the twist: Adding details always makes scenarios less probable. A person can’t be more likely to fit two conditions than one.

Steve’s case hits harder. His shy demeanor and love for detail made 70% of participants call him a librarian. Reality check: There are 20 male farmers for every male librarian in America. Our brains cling to personality stereotypes while ignoring simple math.

When Fast Thinking Fails Us

Quick judgments might seem smart at first, but they often lead to trouble. Nobel research reveals that people often misinterpret randomness. They ignore the statistical odds and let common traits cloud their judgment.

This is why gamblers keep betting even when they’re losing. Investors also get lured into risky startups that look flashy but are not sound. These patterns might feel right, but they’re actually misleading.

When money, safety, or fairness are at risk, these mental mistakes can cost a lot. It’s important to slow down and think more carefully before making decisions.

Representativeness Heuristic Mental Model: Patterns That Fool Us Daily

These laboratory findings mirror real-world judgment errors:

| Scenario | Common Belief | Actual Probability |

|---|---|---|

| Coin flip sequences | HTHTTH “feels” more likely | All 6-flip combos equal |

| Startup founders | “Young dropout” seems typical | Average founder age: 45 |

| Weather predictions | “80% chance of rain” | Means rain in 8/10 similar days |

Gamblers often bet against streaks, thinking “tails is due.” Investors chase stocks that “look” successful. Both mistakes come from trusting apparent patterns over probability rules.

When did you last choose a compelling story over cold facts? That moment holds the key to sharper decisions.

How the Heuristic Impacts Decision Making

Imagine serving on a jury. A defendant matches every stereotype of a “career criminal”—tattoos, rough demeanor, prior arrests. But what if the crime occurred in a city where 99% of similar offenses are committed by first-time offenders? Our brains often cling to surface traits while ignoring critical data.

Overlooking Base Rates and Probabilities

People frequently swap math for stories. A tech startup founder with an Ivy League degree feels more likely to succeed than a community college grad—even when market data shows otherwise. This happens because vivid details overpower statistical truths.

Three common patterns emerge:

- Job interviews where charisma beats qualifications

- Medical diagnoses favoring obvious symptoms over rare conditions

- Investments chasing “hot” stocks despite poor fundamentals

| Situation | What We Focus On | What We Ignore |

|---|---|---|

| Hiring salespeople | Confident personality | Past performance data |

| Weather forecasts | “80% chance” label | Regional climate history |

| Product launches | Exciting prototypes | Market saturation rates |

Even experts stumble. Doctors sometimes misdiagnose common illnesses as exotic ones after watching medical dramas. Investors might back flashy startups while overlooking stable index funds. The fix? Ask: “What numbers am I dismissing because they lack drama?”

When did you last choose a compelling narrative over boring-but-accurate stats? That moment holds your next growth opportunity.

Sector-Specific Effects and Implications

A hospital patient’s fate shouldn’t depend on their appearance—but sometimes it does. From courtrooms to corporate offices, snap judgments based on surface traits shape outcomes in critical fields. Three areas show particularly strong effects: healthcare, finance, and hiring.

Influence in Courts, Medicine, and Finance

Doctors often miss COPD diagnoses in women because the condition feels more “typical” in men. Studies show female patients face longer diagnostic delays—even when symptoms match. Similarly, jurors might perceive a tattooed defendant as more likely guilty, despite no direct evidence.

| Field | Common Error | Reality Check |

|---|---|---|

| Healthcare | Assuming heart attacks only affect overweight patients | 35% of female heart attacks lack chest pain |

| Finance | Chasing “hot” stocks that mirror past winners | 82% of actively managed funds underperform indexes |

| Legal | Judging credibility based on speech patterns | Verbal fluency doesn’t correlate with truthfulness |

Impact on Hiring Practices and Stereotyping

Car dealerships often limit test drives to customers matching their “ideal buyer” profile. In workplaces, managers might favor candidates who share hobbies with existing team members. This creates homogeneous teams—one study found 72% of hires resembled their interviewers in background or appearance.

Three costly consequences emerge:

- Overlooking qualified candidates from non-traditional paths

- Reinforcing industry stereotypes (e.g., “tech people should code since age 12”)

- Reducing innovation through lack of diverse perspectives

When did your last decision favor someone who “fit the mold” over someone who challenged it? That moment reveals where growth begins.

Role of Media and Pop Culture in Reinforcing Heuristics

TV shows, news, and social media shape our mental images. They show us “typical” characters like tech bros or doctors. These images become our go-to ideas over time.

This is important because media stereotypes often hide real diversity. For example, people might think hackers are all young men, even though they come from many backgrounds. Or they might think lawyers always have a certain accent or wear suits.

In decision science, this is called “availability bias.” It’s when we remember vivid examples too much. This, along with the representativeness heuristic, makes us judge based on what we see a lot. The more we see a pattern, the more we expect it, and judge by it.

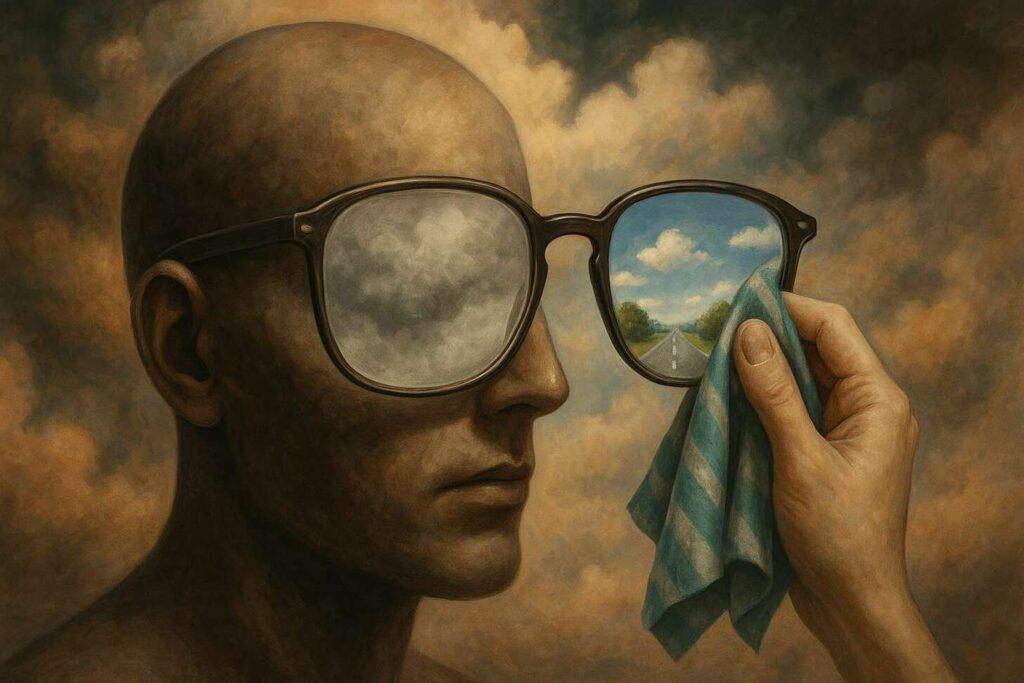

Recognizing and Overcoming Cognitive Biases

Every choice you make starts with a story your brain tells itself. Like foggy glasses distorting a view, biases can blur reality when we rely on quick assumptions. The key lies in spotting these hidden filters—then cleaning the lens.

Identifying When Stereotypes Skew Judgment

Notice moments when beliefs feel certain without evidence. A hiring manager might favor candidates who share their hobbies during an event. A doctor could dismiss rare symptoms that don’t match textbook cases.

These errors judgment often stem from trusting familiar patterns over fresh information in an event based context.

Strategies for Critical Thinking

Pause when decisions feel automatic. Ask: “What facts am I ignoring?” Try these tactics:

- Seek base rates: Research statistical probabilities before acting

- Challenge comparisons: Ask if similarities truly predict outcomes

- Embrace uncertainty: Label assumptions as “possible” rather than “certain”

Slowing your thinking process creates space for better judgment. Like checking mirrors while driving, regular reality checks help navigate around mental blind spots. When did you last question a snap conclusion? That awareness could be your next breakthrough.

Breaking the Loop: How to Unlearn Mental Templates

Unlearning bias isn’t about being perfectly objective. It’s about making better guesses. One way is to imagine unlikely scenarios. For example, what if the coder is a retiree? Or what if the heart attack patient is a young woman?

Other tools help too. Blind screening in hiring or double-checking assumptions with data are good examples. These methods make us slow down. This is exactly what we need to avoid flawed mental shortcuts.

With practice, this change becomes automatic. Your brain starts to think, “What else could be true?”

Conclusion

The representativeness heuristic mental model shows how we often let surface traits or familiar patterns override logic. It affects decisions in courtrooms, boardrooms, hospitals, and daily life. It shapes our choices more than we think.

Learning about this mental shortcut isn’t about getting rid of it. It’s about recognizing when it happens. When something “feels right,” that’s a sign to slow down. Ask yourself: Does this match reality, or just a stereotype I’ve seen before?

Try to pause, seek real data, and question mental templates. This small change can lead to fairer hiring, smarter investments, and better judgments in all areas of life.