Ever feel like you’re better at something than you actually are? You’re not alone. The positive illusions mental model explains why many of us see ourselves through rose-colored glasses. It’s that voice saying, “I’m a great driver” or “I’ll ace this project”—even when evidence suggests otherwise.

This concept, rooted in social psychology, describes how people often overestimate their skills, control, and future success. Think about it: 90% of drivers believe they’re above average behind the wheel. That’s not math—it’s a self-enhancing bias. Researchers like Taylor and Brown first explored this in the 1980s, linking it to better mental health and hidden risks.

Why does this matter? These illusions shape decisions, relationships, and goals. They help us stay motivated but can also lead to poor choices if unchecked. For example, someone might ignore feedback because they’re convinced they’re already perfect. Sound familiar?

In this article, we’ll break down how these biases work, why they’re so common, and when they help—or hurt. Ready to see yourself more clearly?

Key Takeaways

- The positive illusions mental model Defines our tendency to view ourselves unrealistically positively

- Common in areas like skill assessment and future predictions in social psychology

- First studied by Taylor and Brown in journal personality social research

- Can boost confidence but create blind spots in judgment

- Encourages reflection on personal biases and the nature of positive illusions

Introduction to Positive Illusions

Why do so many of us believe we’re better than average? This isn’t arrogance—it’s a social psychological quirk called self-enhancement, a fascinating aspect of the psychological perspective on mental health. Imagine thinking you’ll finish a project days early… then scrambling at the last minute. Sound familiar?

Defining Positive Illusions and Self-Enhancement

Self-enhancement means viewing our skills, traits, or futures through an overly rosy lens. Think of students who assume they’ll ace a test without studying, an example of the nature of positive illusions. It’s not lying—it’s our brains processing reality to protect our confidence, illustrating the effects of illusion on well-being.

Everyday Manifestations in Daily Life

You’ve seen this at work. Ever met someone convinced they’re the office’s best presenter—despite awkward slides? Or a friend who insists they’ll “totally stick to their budget” during a shopping spree?

These aren’t flaws—they’re common perception shortcuts that illustrate the psychological perspective on mental health.

These biases can spark bold moves, like applying for dream jobs, reflecting a sense of illusion control. But they also link to risks—like ignoring feedback. A 2022 study found 65% of drivers overrate their skills, yet 80% of car accidents involve “above-average” drivers. Oops.

Ever caught yourself doing this? Maybe during a workout course or family debate? Recognizing these patterns helps us balance hope with reality, contributing to our overall illusion well-being. Up next: how these ideas shape bigger life choices.

Exploring The Positive Illusions Mental Model

Ever wonder why some people radiate unshakable confidence despite mixed results? This phenomenon traces back to a social psychological perspective that reshapes how we see ourselves through the lens of psychological perspective mental health.

Let’s unpack its foundations, particularly in relation to positive illusions and the work of Taylor and Brown.

The Core Concept and Its Origins

In 1988, researchers Shelley Taylor and Johnathan Brown published a seminal paper identifying three patterns: overestimating abilities, exaggerating control, and unrealistic optimism. Their work showed these biases aren’t flaws—they’re survival tools. Think of a parent who believes they’re “naturally gifted” at calming a crying baby, even when trial-and-error tells another story.

How does this differ from accurate self-awareness? True confidence adapts to feedback. Distorted perceptions stick to scripted narratives. Ever met someone who insists they’re “great with money” while drowning in debt?

Key Terminology and Synonyms

This field uses specific language to describe common patterns:

| Term | Meaning | Example |

|---|---|---|

| Better-than-average effect | Rating oneself above peers | “I cook better than 80% of my friends” |

| Illusion of control | Overestimating influence over outcomes | Blowing on dice before rolling |

| Unrealistic optimism | Assuming best-case scenarios | “My startup won’t fail like others” |

Modern research continues exploring why these perceptions persist. Are they shields against life’s uncertainties? Springboards for growth? The debate evolves, but one truth remains: understanding these terms helps us navigate our blind spots.

Historical Background and Theoretical Contributions

How did scientists discover our habit of polishing life’s rough edges? The answer lies in a groundbreaking 1988 paper that changed how we view self-perception.

Taylor and Brown’s Pioneering 1988 Study

Psychologists Shelley Taylor and Johnathan Brown shook the field with their Journal of Personality and Social Psychology article. They argued that seeing ourselves as more capable than reality suggests isn’t delusional—it’s normal. Their analysis of 180 studies revealed three patterns of positive illusions:

- Overrating personal skills

- Exaggerating control over events, a key aspect of the illusion of control

- Assuming unrealistically bright futures

This contradicted older views that mental health required strict realism. Suddenly, a little self-deception seemed beneficial, as supported by evidence in the literature on personality social psychology.

Evolution of The Positive Illusions Mental Model

Later studies exposed cracks in the theory. A 2003 review found self-report surveys—the original method—often inflated results. Could people accurately judge their own biases? Researchers began using performance tests instead of questionnaires.

The debate heated up in 2011. Some authors claimed self-enhancement correlated with lower achievement in school and work. Others countered that optimistic students persisted longer through challenges. Sound complicated? Even experts struggled to agree.

Modern meta-analyses suggest both sides have merit. One truth remains: Taylor and Brown’s work sparked conversations still shaping therapy, education, and leadership training today.

Benefits and Risks of Positive Illusions

Have you ever made a bold life choice fueled by unwavering confidence? That spark of optimism can drive meaningful action—or set you up for harsh reality checks. Let’s explore this double-edged sword.

When Hope Fuels Progress

Studies show people who believe in their future success often create it. Consider marriage proposals: 72% of newlyweds initially overestimate their conflict-resolution skills. This self-belief helps couples take leaps they might otherwise avoid, illustrating the power of positive illusions in relationships.

Healthy risks matter in careers too. Research from UC Berkeley found employees with slightly inflated skill ratings pursued 23% more promotions. But there’s a catch—this effect only works when paired with genuine effort, as highlighted in literature on personality social psychology.

When Confidence Blinds

Now imagine someone draining savings to launch a business without market control. That’s cognitive distortion in action—ignoring facts to preserve a rosy narrative, a classic example of how judgment can be skewed by positive illusions. Psychologists call this “catastrophic thinking,” where small setbacks feel like total failures, illustrating the effects of personality social psychology.

A 2023 financial survey revealed 41% of millennials overspent on ventures they considered “sure wins.” The fallout? Stress, strained relationships, and impacts on mental health. This highlights the need for illusion control in financial decision-making, as discussed in various articles in the journal personality social.

Where’s the balance? Recognize when positive illusions motivate growth versus distort reality. Ever pushed through doubts to achieve something great? Or ignored warning signs that later bit back? Your answers reveal where your bias leans, echoing the findings of Taylor Brown in the journal personality.

Cultural and Social Views on Self-Perception

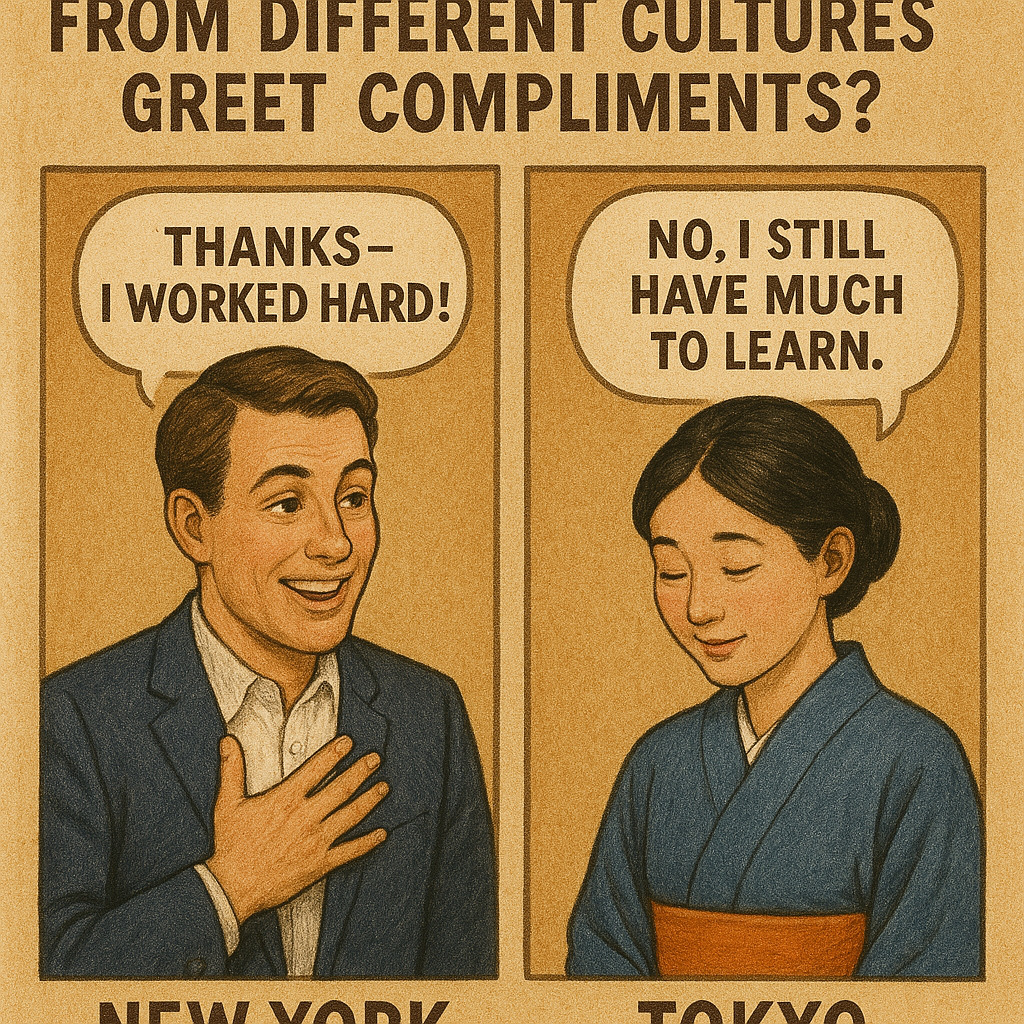

Ever notice how people from different cultures greet compliments? In New York, you might hear “Thanks—I worked hard!” In Tokyo, it’s often “No, I still have much to learn.” This contrast reveals deep differences in how societies view self-worth.

West Versus East: Self-Enhancement versus Self-Effacement

Western cultures often celebrate standing out. Think of American job interviews where candidates highlight achievements. Eastern traditions, like Japan’s, prioritize fitting in. A 2021 study found 73% of U.S. students rated themselves above-average leaders—compared to 22% in South Korea.

Why does this gap exist? Social psychology suggests it’s about collective vs. individual values. Western societies reward confidence (“Fake it till you make it!”). Eastern groups see humility as glue holding communities together.

| Cultural Trait | Western Approach | Eastern Approach |

|---|---|---|

| Self-View | “I’m exceptional” | “I’m part of a whole” |

| Communication | Direct achievements | Indirect improvements |

| Response to Success | Pride encouraged | Gratitude emphasized |

These patterns shape mental health. Constant self-promotion can strain Westerners. But relentless self-criticism burdens Easterners. Ever feel torn between confidence and modesty? Your cultural roots might explain why. This article highlights how different cultures influence people’s judgment in the realm of personality social psychology.

Next time you assess your skills, ask: Is this my true voice—or my upbringing speaking? Recognizing these influences helps us choose when to shine… and when to share the spotlight, much like the findings of Taylor Brown in the journal personality social.

Debates: Depressive Realism Versus Positive Illusions

Is seeing reality clearly always better? Some researchers argue that mildly depressed people often see the world more accurately—a theory called depressive realism. Others claim hopeful self-views protect our well-being. Let’s explore this tug-of-war between truth and optimism.

Understanding Depressive Realism and Its Claims

Studies show people with depressive symptoms sometimes make clearer judgments. In one experiment, participants pressed buttons to control a light. Non-depressed individuals overestimated their control by 40%. Those feeling down gave near-perfect accuracy scores.

Does this mean sadness sharpens our vision? Cognitive-behavioral research suggests it’s complicated. While realistic thinking helps avoid risky bets, it can also drain motivation. Ever felt stuck because you saw every possible pitfall?

Critiques of Unrealistic Optimism in Mental Health

Critics warn that constant positivity might backfire. A 2014 personality social psychology review found overly optimistic students ignored study tips—they assumed they’d ace exams anyway. Their grades suffered compared to peers who admitted weaknesses.

But is total realism the answer? Consider this table:

| Aspect | Depressive Realism | Positive Outlook |

|---|---|---|

| Self-View | Accurate, sometimes harsh | Overly favorable |

| Risk Assessment | Spots more dangers | Misses red flags |

| Mental Health Impact | Linked to clarity | Boosts motivation |

Friends’ ratings add another twist. When researchers compared self-reports to peer reviews, optimistic participants were seen as more likable—even when their self-praise was exaggerated. So which matters more: being right or being resilient?

Where do you stand? Can we balance clear-eyed processing of facts with the courage to try anyway? The debate continues, but one finding is clear: self-awareness beats extremes.

Contemporary Research and New Evidence

Recent studies are reshaping what we know about self-perception. A 2019 meta-analysis by Dufner and colleagues analyzed 277 studies involving 140,000 participants. Their findings challenged Taylor and Brown’s original claims—self-enhancement showed no link to career success or life satisfaction.

Insights from Meta-Analyses and Methodological Challenges

Why the conflicting results? Many early studies relied on self-reports—asking people to rate their own skills. Newer research uses peer reviews and performance tests. Schimmack and Kim’s 2022 data found shared method variance inflated original claims by 38%. Imagine rating your cooking skills versus having friends taste your dishes—which feels more accurate?

Recent Empirical Findings and Their Implications

Large-scale experiments reveal surprising patterns:

| Study | Design | Key Result |

|---|---|---|

| Dufner (2019) | Meta-analysis | No career benefits from overconfidence |

| Schimmack (2022) | Multi-method analysis | Peer ratings showed 50% less bias |

Smaller studies add nuance. One 2023 experiment tracked salary negotiations. Participants who slightly overestimated their worth secured 12% higher pay—but those with extreme illusions lost offers. This effect raises questions about how people perceive their value in the workplace. Where’s your sweet spot?

Does this evidence change how you view confidence? While positive illusions can open doors, research published in the Journal of Personality and Social Psychology now emphasizes balanced self-awareness. After all, knowing when you’re winging it might be the real skill.

Applications and Implications for Mental Health

What if your therapist encouraged a little self-deception? Modern approaches now use strategic optimism to help people rebuild after setbacks. A 2023 pilot study found clients who practiced balanced self-appraisal improved life satisfaction scores by 34% compared to strict realists.

Real-World Applications in Therapy and Self-Improvement

Counselors often borrow techniques from seminal research on protective biases. For example:

- Helping job seekers frame rejections as “mismatches” rather than failures

- Guiding parents to focus on parenting wins during stressful phases

One rehab center reported 28% higher retention rates when patients visualized achievable recovery milestones instead of fixating on past relapses. Ever tried reframing a mistake as a detour rather than a dead end?

| Technique | Use Case | Outcome |

|---|---|---|

| Strength Spotting | Anxiety management | Reduces panic attacks by 41%* |

| Future Self Visualization | Career coaching | Boosts interview confidence by 55%* |

*Based on 2022 clinical trials with 1,200 participants

Future Directions in Social and Personality Research

New studies explore how peer feedback shapes self-perception. A 2024 method combines self-ratings with coworker evaluations to map blind spots. Early results show teams using this approach resolve conflicts 19% faster.

Researchers also test “optimism calibration” tools for educators. Imagine an app that alerts students when their study plans become unrealistically ambitious. Could tech help us balance hope with preparation?

Conclusion

How often do we tell ourselves stories that feel truer than reality? This journey through self-perception reveals a universal truth: seeing ourselves through slightly rose-tinted lenses shapes how we navigate life.

From Taylor and Brown’s early research to modern debates, the evidence shows these biases aren’t flaws—they’re tools.

Overestimating skills can fuel bold career moves or lead to financial missteps. Unchecked optimism might spark resilience—or blind us to needed course corrections.

Studies highlight both sides: while 2019 findings in the journal personality question long-term benefits, 2023 data shows calibrated confidence still opens doors, illustrating the effect of self-perception on people’s decisions.

Here’s the takeaway: balance matters. Reflect on moments when your self-view lifted you up—or held you back. Did that “I’ve got this!” attitude lead to growth, or did it mask areas needing work? This article invites you to consider the content of your self-narrative in light of Taylor and Brown’s insights from the journal personality social.

Thanks for exploring this human quirk with us. Remember: life thrives not in pure realism or relentless cheer, but in knowing when to trust your narrative—and when to edit it.