Ever walked into a store and saw a “$499” price tag cut to $299? This immediate impression, studied extensively by psychologists, influences our perception of value. It shows the anchoring bias mental model in action.

In psychology and economics, anchoring bias is a strong cognitive bias. Anchoring bias is a powerful cognitive bias found in psychology and economics. It makes the first piece of information you see shape your choices, even if it’s not important. This is seen a lot in real estate, where the first price you see sets your expectations.

Psychologists and economists have studied anchoring and decision theory a lot. They found that once an anchor is set, later changes are often not enough. This highlights how much the first information can affect us.

The anchoring bias affects mental model many areas, like salary talks and real estate prices. It also impacts investment choices and medical decisions. Our brains look for quick solutions, often sticking to the first idea we get.

This can lead to bad choices and expensive mistakes. It’s a big problem because we might not realize we’re making a wrong decision.

Key Takeaways

- Anchoring bias mental model: First impressions shape decisions, even if they’re unrelated to the situation

- Negotiations, purchases, and financial choices often revolve around initial numbers

- This pattern works like a mental shortcut to simplify complex choices

- Awareness helps identify when irrelevant information influences you

- Practical strategies exist to reduce its impact on daily decisions

By understanding this hidden influence, you gain power. You’ll start spotting anchors everywhere—and learn how to swim against their current.

Why Anchoring Bias Matters in Everyday Life

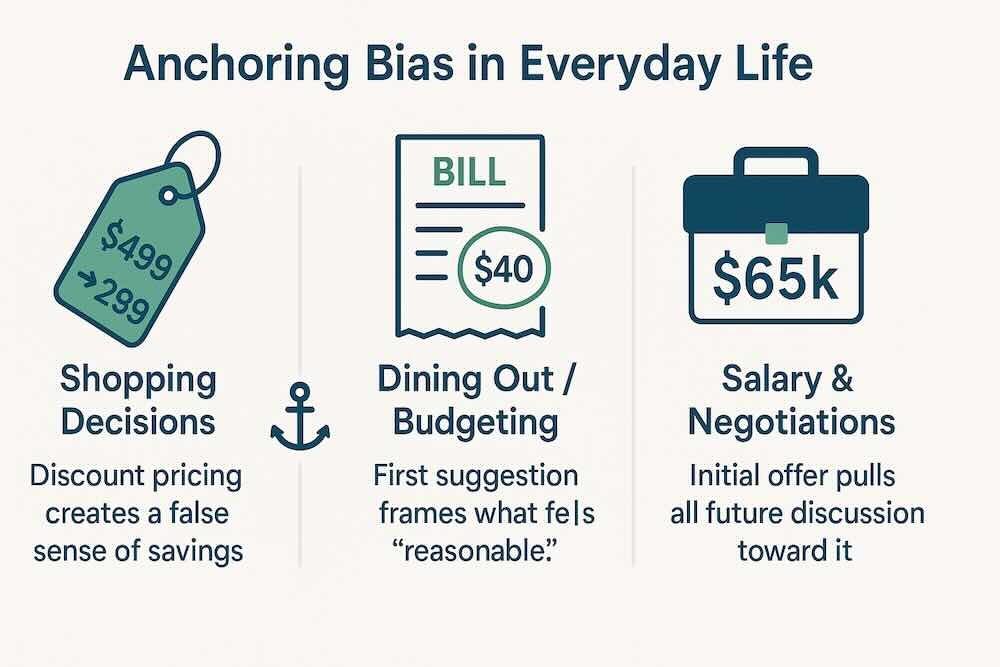

Anchoring bias isn’t just for experts. It affects our daily choices. From grocery prices to salary talks, the first number we see influences everything.

Think about online shopping. They show the original price before the discount. Even if the sale price is higher than others, we feel like we’re saving. Friends suggesting a $40 restaurant budget also sets our expectations.

Knowing about the anchoring bias mental model helps us think twice about first numbers. By questioning them, we avoid being swayed by hidden influences. This protects our finances, career, and relationships.

Introduction to the Anchoring Bias Mental Model

Ever test driven a car after hearing the salesperson mention “most buyers pay $35,000”? It makes every feature seem worth that price. This shows how the first piece of information can shape our choices more than we think.

The anchoring effect shows how this initial information can sway our decisions. It reveals biases we often overlook. It’s a powerful force in how we make choices.

Anchoring Bias Mental Model Definition and Core Concepts

Your brain treats the first number or fact it encounters like a ship’s anchor. Once dropped, it resists moving far even with new data. Nobel-winning researchers Tversky and Kahneman proved this through experiments showing how random starting points skew estimates by 20-50%.

Imagine house hunting. If the realtor opens with “This neighborhood averages $800k,” your budget suddenly feels flexible. The initial figure becomes a gravitational center for all negotiations—even if it’s outdated or irrelevant.

Overview of Its Impact on Decision-Making

This pattern warps professional evaluations too. Hiring managers offered lower salary ranges for a role often finalize offers closer to that initial number. Juries sentencing defendants hear prosecutors’ suggested penalties first—and rarely deviate far from them.

Three critical insights emerge:

- Early numbers create invisible boundaries

- Adjustments from starting points remain insufficient

- Irrelevant anchors still sway outcomes

Recognizing this pull helps you pause. Ask: “Would I accept this number if it were 30% higher or lower?” That simple question creates mental space to evaluate choices clearly.

Origins and Theoretical Foundations

What if a spinning wheel could predict how you’d answer a geography question? In 1974, two psychologists designed an experiment that changed how we understand decision-making forever, revealing the first piece of information that can influence our thought processes and heuristics biases.

Tversky and Kahneman’s Pioneering Work

Amos Tversky and Daniel Kahneman asked people to estimate the percentage of African countries in the UN. First, they spun a wheel showing either 10 or 65. Those who saw 65 guessed nearly twice as high as the 10 group—even though everyone knew the wheel was random.

The same team tested number sequences like 8×7×6… versus 1×2×3… Despite identical answers, estimates differed wildly based on starting digits. Studies show our brains grab onto the first piece of information we get.

This information becomes the starting point for all our thoughts afterwards. This process is linked to the Heuristics Mental Model. It explains how we use mental shortcuts to make decisions.

This idea is key in behavioral psychology. It’s also well-studied by The Decision Lab.

From Lab to Real World

Their paper “Judgment Under Uncertainty” introduced heuristics—mental shortcuts we use when facing complex choices. The anchoring effect became a cornerstone of behavioral economics, explaining why car prices and courtroom demands sway decisions.

Three key lessons emerged:

- First numbers create invisible boundaries

- Adjustments from anchors often stay too small

- Even absurd starting points influence outcomes

Today, this theory helps explain stock trades and holiday sales alike. By understanding where these patterns began, we gain tools to spot them in daily life.

Cognitive Mechanisms Behind Anchoring

Have you ever judged a book by its opening paragraph, ignoring later chapters that changed the story? Our brains work similarly when processing numbers and ideas in various negotiation situations.

The first detail we encounter often becomes the foundation for every decision that follows, serving as an example of how personality effects can shape our choices.

The American Psychological Association says anchoring bias is when we overvalue the first piece of information we get. This happens when we’re unsure about something. It makes us focus more on information that matches the first thing we heard, making it hard to adjust our thinking.

The Role of First Impressions in Shaping Judgments

Your brain files the first piece of information like a priority document. This “primacy effect” explains why initial numbers or ideas stick harder than facts learned later. Think of it as mental bookmarks—once placed, they guide how we interpret everything afterward.

Studies reveal this tendency isn’t accidental. When facing new choices, your mind clings to early data points to save energy. Research on cognitive shortcuts in decision-making shows we adjust predictions 40% less than logic demands once an anchor exists.

Insights Into Selective Information Processing

Once an initial value enters your thoughts, the Confirmation Bias Mental Model kicks in. You’ll unconsciously seek details supporting that starting point while downplaying contradictory evidence. It’s like building a puzzle around one corner piece—even if other sections don’t fit.

| Aspect | Primacy Effect | Recency Effect |

|---|---|---|

| Memory Recall | Stronger for first items | Stronger for last items |

| Decision Weight | Anchors judgments | Influences final adjustments |

| Brain Process | Automatic filing | Conscious review |

This process served hunters assessing threats quickly. Today, it can trap us in outdated assumptions. Recognizing this pattern helps pause and ask: “Does this starting point still make sense?”

Real-Life Examples of Anchoring Bias in Action

Ever clicked on a product online because the “original price” made the discount seem irresistible? This everyday scenario reveals how initial numbers, or the first piece of information, steer choices across industries like salary negotiations. Let’s explore two domains where this pattern shapes outcomes dramatically, particularly in situations involving judgment uncertainty and negotiation strategies.

Retail Pricing and Value Framing Strategies

Stores use comparison pricing to create perceived value. A jacket tagged “$499 → $299” triggers urgency, even if the higher price was never realistic. Research shows precise numbers like $255,500 for homes attract better offers than rounded figures—buyers subconsciously view them as more credible.

Real Estate and Jury Decision-Making Studies

Listing prices pull offers within 5-10% of the asking amount. But the courtroom reveals higher stakes. A 2014 study found jurors awarded 43% more in damages when lawyers suggested larger figures first. Initial numbers become invisible boundaries, even when irrelevant.

| Industry | Anchor Strategy | Outcome |

|---|---|---|

| Retail | “Original price” comparisons | 28% sales increase |

| Real Estate | Precise listing prices | 4.2% higher offers |

| Legal | High damage requests | 43% larger awards |

These case studies show how first numbers stick. Next time you see a “limited-time deal,” ask: “Would this price feel fair without the comprison?” Awareness helps you decide based on actual value, not clever framing.

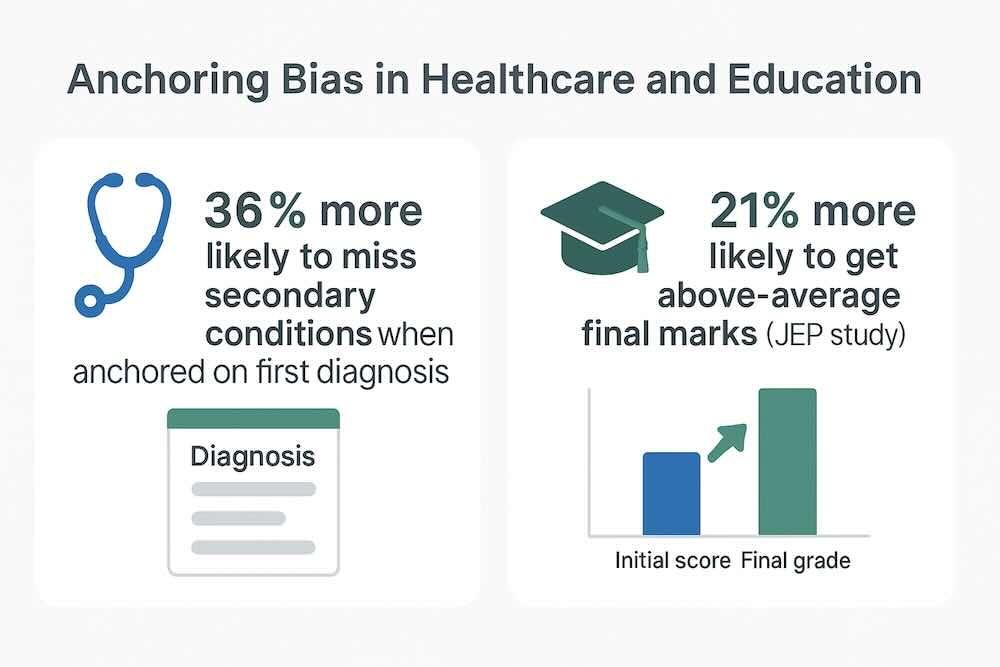

Anchoring Bias in Healthcare and Education

The anchoring bias mental model affects more than just markets and negotiations. It has big impacts in healthcare and education, where being accurate and fair is key. In medicine, the first diagnosis a doctor thinks of can shape all tests and treatments that come after.

A 2021 study in BMJ Quality & Safety showed doctors who start with a diagnosis are 36% more likely to miss secondary conditions. For instance, a patient with flu-like symptoms might get treated for the flu, missing signs of pneumonia because the doctor is stuck on the first idea.

In education, early expectations also play a big role. A study in the Journal of Educational Psychology found teachers’ expectations, based on early test scores or classroom behavior, affect final grades.

Students seen as “high achievers” early on were 21% more likely to get high final marks, even if they later did worse. On the other hand, students with low early scores often found it hard to overcome that label, even if they improved later.

Both healthcare and education show the risks of relying too much on first impressions. Doctors and teachers need to actively question their initial thoughts. By looking at data on their own and considering different views, they can avoid unfair or costly decisions.

Anchoring Bias Mental Model in Negotiations

Ever received a job offer that felt lower than expected, yet somehow “reasonable”? That initial figure acts like gravity—pulling discussions toward its orbit. Whether discussing salaries or business terms, the first number mentioned often becomes the invisible ruler measuring all future proposals.

How First Offers Set the Anchor

Imagine discussing a project fee. If a client opens with $10,000, your counteroffer likely stays near that range—even if your usual rate is higher. Research shows first offers influence outcomes by 30-40%. Why? Our brains treat opening numbers as reference points, adjusting from there rather than starting fresh.

In salary talks, employers often benefit from setting the anchor. This is a pattern also explored in the Game Theory Mental Model. According to Program on Negotiation at Harvard, buyers and sellers often see the first offer as their starting point. This mindset shapes their counteroffers and final decisions, even before all terms are agreed upon.

Case Studies on Salary and Deals

A tech startup founder shared how she secured 22% more funding by leading with precise numbers: “$2.37 million” instead of rounded figures. This tactic made her proposal appear data-driven and non-negotiable.

| Scenario | Anchor Strategy | Result |

|---|---|---|

| Job Offer | Employer starts at $65k | Final salary: $68k |

| Consulting Contract | Freelancer proposes $225/hour | Accepted at $210/hour |

| Business Acquisition | Buyer opens with $15M | Closed at $16.2M |

Next time you negotiate, ask: “Would this number feel fair if roles were reversed?” Detaching from the initial figure helps reclaim control of the discussion.

Impact on Investing and Business Decisions

Ever held onto a stock because its past price felt like a safety net? This invisible tether to initial numbers shapes our financial choices more than spreadsheets or market trends. Early figures become invisible rulers in negotiations, influencing every first piece of information presented.

This anchoring bias often leads to skewed perceptions. It’s essential to list out current data against those early figures. This helps us see things more clearly and make better decisions.

When Numbers Become Blindfolds

Morningstar research shows 63% of investors chase funds after strong 12-month performance. That recent high becomes their north star—even when fundamentals shift. A stock dropping from $80 to $40 feels like a steal, though company health might’ve crumbled.

Anchoring Bias Mental Model: The Price Tag Mirage

Business deals face similar traps. Leaders often fixate on a company’s asking price during acquisitions rather than independent analysis. Venture capitalists sometimes overvalue startups based on early projections, ignoring current data.

| Scenario | Anchor Used | Outcome |

|---|---|---|

| Stock Purchase | Previous $100/share peak | Held losing position 73% longer |

| Startup Funding | Initial $5M valuation | Series B round inflated by 18% |

| Product Pricing | Competitor’s $299 launch | Priced 11% below market value |

Hayes’ 2021 study found people base 68% of investment choices on arbitrary starting points. The solution? Ask: “Would I pay this price if the original number vanished?” Detaching from initial figures reveals true value.

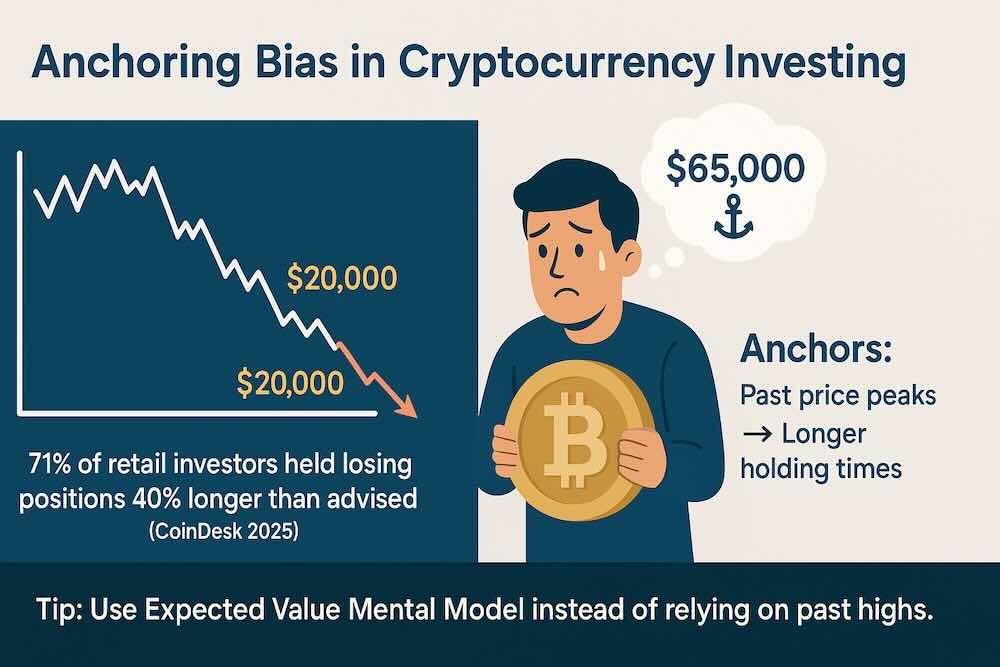

Anchoring Bias in Cryptocurrency Investing

Cryptocurrency markets show how anchoring affects financial choices. When Bitcoin fell from $65,000 to under $20,000, many saw $20,000 as a good deal. This was because the earlier high was their anchor.

In 2025, a CoinDesk study found that 71% of small investors held onto losing crypto positions for 40% longer than they should have. They waited for prices to go back to past highs. This behavior is similar to the anchoring bias in stock trading but is more intense with digital assets.

Experts in behavioral finance warn that these anchors lead investors to overlook important signs. They ignore network activity, regulatory changes, or project usefulness. Instead, they focus on past price peaks.

To fight this, analysts suggest using the Expected Value Mental Model. This model looks at probabilities and possible rewards, not just past highs. It helps investors make better choices and look at long-term value, not just emotional highs.

Anchoring Bias and AI-Assisted Decision-Making

Recent updates in 2024 and 2025 show how anchoring bias affects choices in the AI era. For example, AI-driven stock trading platforms often suggest a “recommended buy-in price” first. A 2024 Financial Times report found that over 58% of users bought shares within 5% of the AI’s first price.

This initial price acts as a digital anchor, influencing decisions. Even when the market later showed a better time to buy, many stuck with the AI’s first suggestion.

In healthcare, the impact is even stronger. A 2025 study in JAMA Network Open showed that doctors agreed with AI’s top diagnosis 64% of the time. This was true even when other diagnoses were more accurate. The study found that even experienced doctors ignored evidence that went against the AI’s first choice.

This highlights that AI doesn’t remove human biases — it often amplifies them.

To fight this, experts suggest reviewing the AI’s second and third options before deciding. By looking at other choices, users can avoid being too influenced by the first one. This approach is similar to strategies in decision theory and cognitive bias research to make more balanced choices.

When Algorithms Inherit Human Shortcuts

AI systems often present their top option first. This becomes an invisible benchmark. Users tend to compare subsequent choices against that opening proposal, even when better alternatives exist. Imagine a compass that’s not quite right. It’s like the first digital suggestion that steers us off track.

This is similar to the OODA Loop Mental Model. Here, the initial direction sets the pace and precision of our choices.

Research analyzing medical diagnoses found doctors using AI tools agreed with flawed recommendations 61% of the time when anchors were present. The anchoring effect persisted despite training and system warnings. This reveals a critical gap: technology processes data, but people still interpret results through biased lenses.

Three patterns emerge:

- First AI outputs frame expectations

- Users undervalue contradictory information

- Overconfidence grows with repeated use

Next time an app suggests a stock trade or workout plan, pause. Ask: “Would I choose this option if it appeared last?” Resetting your mental starting point helps separate useful insights from digital anchors.

How to Overcome Anchoring Bias in Daily Life

Anchoring bias might seem hard to avoid, but research in behavioral economics and psychology offers solutions. The first step is to delay your response when you first hear a number or piece of information.

Just a short pause lets your brain think of other options instead of just accepting the first one.

Studies in decision theory show that waiting 30 seconds during negotiations can cut down anchor influence by almost 25%. This small delay can make a big difference.

Another effective method is to set your own anchor before making a decision. For instance, if you’re getting ready for a job interview, decide on a salary range that matches your skills and the market. Presenting this range first helps control the conversation, not letting the other side’s offer set the tone.

Negotiation experts call this “pre-anchoring,” and it often leads to better results in both work and personal life.

Lastly, use data triangulation by checking different sources before making a choice. When buying a home, don’t just look at the asking price. Look at at least three market analyses or historical data to find a fair price. This method helps you avoid being swayed by just one number.

By using these strategies, you can turn knowing about anchoring bias into a habit. This makes it easier to recognize when an anchor is trying to influence you. With a mix of being mindful, prepared, and using objective data, you can beat one of the biggest cognitive biases in everyday life.

Conclusion

The anchoring bias mental model shows how first impressions shape our choices. This happens when we shop, negotiate salaries, or make big investments. The first number we see can influence our decisions, even if better options are available.

Being aware is key. By taking a moment to think, setting our own anchors, and checking our choices with more data, we can overcome these biases. This is important for leaders, investors, and anyone who makes decisions.

Learning about the anchoring bias helps us make better choices. To improve even more, look into other mental models like the Confirmation Bias Mental Model, the Game Theory Mental Model, and the Expected Value Mental Model. These models offer strategies to fight biases and solve problems more effectively.