This model comes from chemistry and is applied to psychology and productivity. Just like molecules need a burst of energy to ignite a reaction, humans need a spark to overcome inertia.

In this article, you’ll learn how this model explains procrastination, how to reduce friction in your daily routine, and how to spark lasting action with practical strategies.

What is Activation Energy? The Science Behind Getting Started

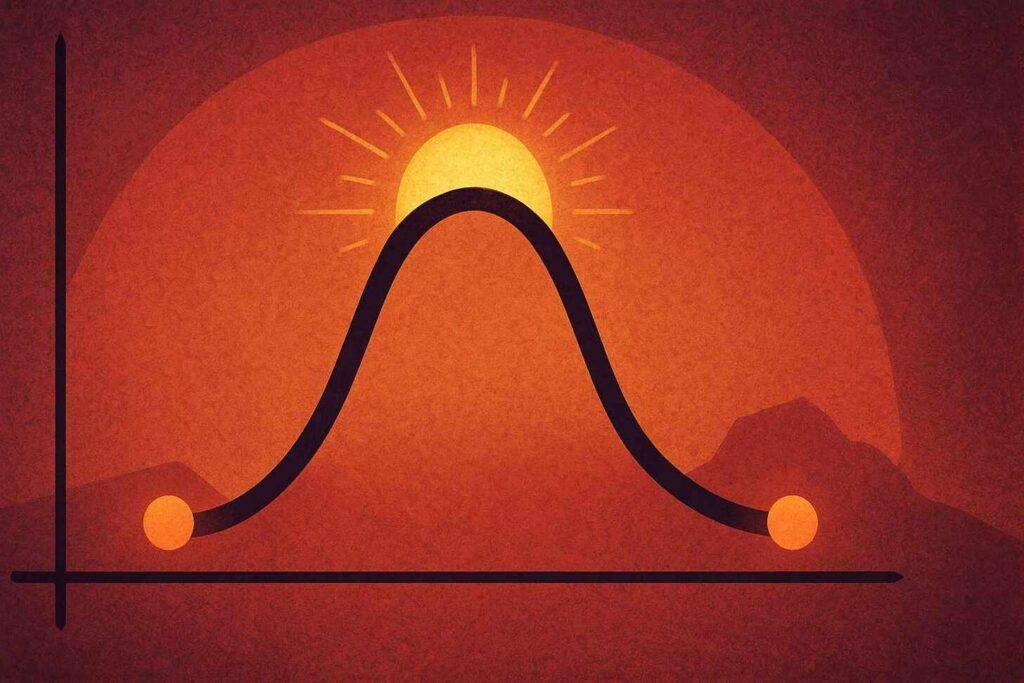

The activation energy curve illustrates why starting is harder than continuing

Activation energy originated in chemistry, where it describes the minimum energy required to start a chemical reaction. Swedish scientist Svante Arrhenius first identified this concept in 1889, developing an equation that shows how chemical reactions need an initial energy push to get going.

Think about lighting a fire. You can’t just place a match against a large log and expect it to burst into flames. You need kindling, perhaps some paper, and enough heat to reach the threshold where combustion begins.

Once the fire starts, it generates its own heat and becomes self-sustaining. That initial energy requirement—the match, the kindling, the effort—represents activation energy.

As a mental model, activation energy helps us understand why:

- Starting a new habit is harder than maintaining one

- The first step of any project often feels the most difficult

- We procrastinate even on tasks we know are important

- Small obstacles can prevent us from taking action

- Momentum makes continuing easier than starting

Just as chemical reactions need that initial push, human behavior follows the same pattern. The energy required to start studying, exercising, writing, or tackling any challenging task is disproportionately higher than the energy needed to continue once you’ve begun.

The Psychology of Friction: Why We Resist Getting Started

Our brains are wired to conserve energy. From an evolutionary perspective, this makes perfect sense—our ancestors needed to save energy for hunting, gathering, and surviving. Today, this energy-conservation instinct manifests as resistance to starting tasks that require significant mental or physical effort.

Psychologists call this resistance “friction,” and it comes in several forms:

Cognitive Friction

The mental effort required to plan, organize, and initiate a task. This includes decision fatigue, overthinking, and the paradox of choice.

Emotional Friction

Fear of failure, perfectionism, and anxiety about the outcome. These emotional barriers can paralyze us before we even begin.

Environmental Friction

Physical obstacles in our surroundings that make starting harder, like distractions, disorganization, or lack of necessary tools.

Habitual Friction

The pull of existing routines and the comfort of the status quo, making new behaviors feel unnatural and difficult.

Temporal Friction

The perceived time cost of starting a task, especially when we overestimate how long something will take.

Social Friction

Lack of support or accountability from others, or social environments that discourage the behavior you’re trying to adopt.

Understanding these sources of friction helps explain why we procrastinate even on tasks we genuinely want to complete. The key insight is that by reducing these friction points, we can lower the activation energy required to start.

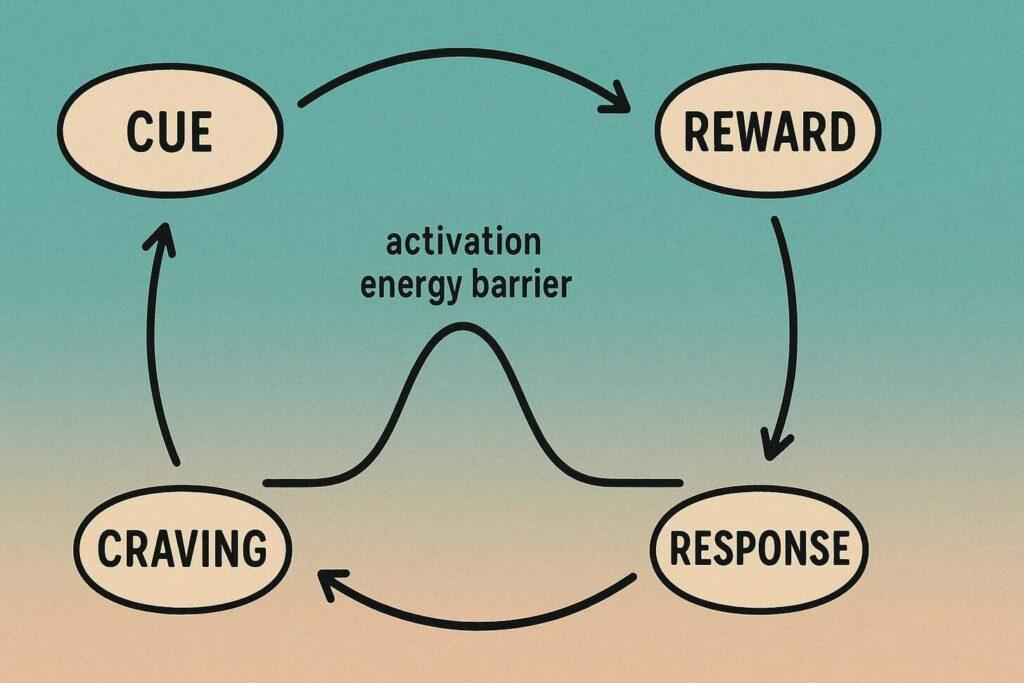

The habit loop with activation energy barrier between intention and action

When we understand activation energy as a mental model, we can design our environments, routines, and mindsets to make starting easier. This is where the real power of this concept comes into play.

5 Laws of Activation Energy Design: Practical Strategies for Taking Action

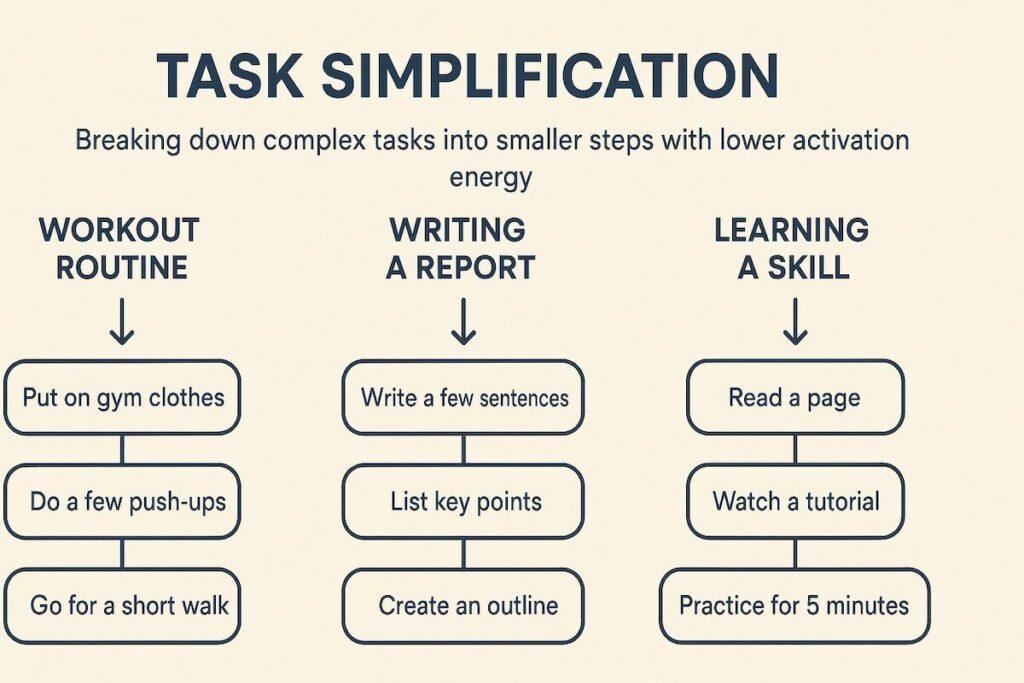

Based on behavioral science and the activation energy mental model, here are five principles you can apply to overcome procrastination and take consistent action:

Law 1: Reduce Activation Energy for Positive Habits

The less energy required to start a positive habit, the more likely you are to do it. Here’s how to lower the activation energy for behaviors you want to encourage:

- Prepare in advance: Lay out your workout clothes the night before, prep ingredients for healthy meals, or set up your desk for tomorrow’s work session.

- Use the two-minute rule: Commit to just two minutes of any activity. Often, starting with this tiny commitment leads to completing the full task.

- Create triggers: Link new habits to existing routines. For example, “After I brush my teeth, I’ll meditate for five minutes.”

- Eliminate decisions: Automate choices by creating systems. Have a Monday workout routine, a Tuesday writing schedule, etc.

- Start with a micro-habit: Make the initial behavior so small it feels ridiculous to skip it. One pushup, writing one sentence, or reading one page.

Law 2: Increase Activation Energy for Negative Habits

Make unwanted behaviors harder to start by adding friction:

- Create distance: Put temptations physically farther away. Store junk food in hard-to-reach places or keep your phone in another room while working.

- Add steps: Introduce extra steps before unwanted behaviors. For example, use website blockers that require you to type a long password to access distracting sites.

- Use commitment devices: Create consequences for unwanted behaviors, like giving money to a friend if you break your commitment.

- Modify your environment: Remove triggers for bad habits. If you snack while watching TV, don’t keep snacks in the living room.

- Increase awareness: Add reflection points before unwanted behaviors. Ask, “Is this helping me achieve my goals?” before engaging.

Law 3: Use Catalysts to Lower Activation Thresholds

In chemistry, catalysts reduce the activation energy needed for a reaction. In behavior change, catalysts include:

- Accountability partners: Share your goals with someone who will check in on your progress.

- Social commitment: Make public declarations about your intentions to leverage social pressure.

- Rewards: Create immediate positive reinforcement for taking action.

- Visualization: Mentally rehearse the process of starting to reduce uncertainty and resistance.

- Momentum triggers: Use music, specific phrases, or rituals that signal “it’s time to begin.”

Law 4: Design Your Environment for Success

Your physical surroundings dramatically impact activation energy:

- Create dedicated spaces: Designate specific areas for specific activities to trigger the right mindset.

- Reduce distractions: Minimize interruptions that increase the activation energy needed to refocus.

- Use visual cues: Keep reminders of your goals visible to maintain motivation.

- Optimize for convenience: Arrange your environment so that positive behaviors require minimal effort.

- Build resource stations: Group necessary tools together so everything you need is readily available.

Law 5: Harness the Power of Momentum

Once you’ve started, use these strategies to maintain progress:

- Use Hemingway’s technique: Stop work at an exciting point so it’s easier to resume later.

- Track progress: Maintain visible records of your consistency to motivate continued action.

- Create success spirals: Build confidence through small wins that lead to bigger accomplishments.

- Establish minimum viable efforts: Set non-negotiable minimums for days when motivation is low.

- Celebrate process over outcomes: Reward yourself for taking action, regardless of results.

Breaking down complex tasks to lower activation energy requirements

Real-World Applications: Case Studies in Overcoming Activation Energy

Case Study 1: Building a Consistent Fitness Routine

Sarah struggled for years to maintain a regular exercise habit. Every few months, she would make ambitious plans to work out five days a week for an hour each session. Her enthusiasm would last a week or two before fading.

After learning about the activation energy mental model, Sarah redesigned her approach:

- She placed her workout clothes and shoes next to her bed each night

- She committed to just 10 minutes of exercise each morning

- She joined a class with a cancellation fee to add accountability

- She prepared her post-workout protein shake the night before

- She tracked her consistency with a simple calendar system

By drastically lowering the activation energy required to start exercising, Sarah has maintained her routine for over eight months. Most days, she continues beyond the initial 10 minutes, but knowing she only needs to commit to that small amount makes starting much easier.

Case Study 2: Overcoming Writer’s Block

Michael, an aspiring novelist, found himself paralyzed by the blank page. The activation energy required to start writing seemed insurmountable as he worried about quality, plot development, and whether his ideas were good enough.

His solution involved several activation energy hacks:

- He created a pre-writing ritual of making tea and lighting a candle

- He ended each writing session mid-sentence to make restarting easier

- He committed to writing just 50 words per day, no matter what

- He used a distraction-free writing app that opened to his current project

- He joined a writing group that expected weekly submissions

Michael completed his first draft in six months, averaging far more than his minimum daily word count. By focusing on lowering the activation energy to begin writing each day, he overcame the psychological barriers that had previously stopped him.

Case Study 3: Building a Meditation Practice

Alex wanted to develop a meditation practice but found it difficult to consistently make time for it. Despite understanding the benefits, the activation energy required to sit down and meditate felt too high amid a busy schedule.

Alex’s strategy focused on making meditation the path of least resistance:

- He created a dedicated meditation corner in his home with a cushion always ready

- He started with just one minute of meditation per day

- He paired meditation with his morning coffee routine

- He used a meditation app with reminders and tracking features

- He placed his phone in “do not disturb” mode during his scheduled meditation time

After three months, Alex’s meditation practice became a natural part of his day. By understanding and addressing the activation energy barriers, he transformed a sporadic activity into a consistent habit.

Tools and Templates: Practical Resources for Applying the Activation Energy Model

The Friction Audit Worksheet

Use this simple tool to identify and eliminate sources of friction in any habit or task you’re struggling to start:

| Friction Type | Questions to Ask | Solutions to Consider |

| Cognitive Friction | What decisions am I facing before starting? What’s unclear about how to begin? | Create checklists, templates, or decision rules. Break tasks into explicit next actions. |

| Emotional Friction | What fears or negative emotions arise when I think about this task? What’s the worst that could happen? | Use mindfulness techniques, reframe the task as an experiment, or focus on process rather than outcome. |

| Environmental Friction | What in my physical environment makes this harder? What tools or resources am I missing? | Reorganize your space, eliminate distractions, or create a dedicated area for the activity. |

| Habitual Friction | What existing habits compete with this new behavior? What routines could I leverage? | Use habit stacking, replace rather than eliminate habits, or create transition rituals. |

| Temporal Friction | When am I trying to do this? Is this the optimal time? How long do I think it will take? | Schedule activities when energy is highest, use time blocking, or commit to shorter time periods. |

The Minimum Viable Action (MVA) Framework

For any goal or habit you’re pursuing, define these three levels of action:

1. The Ideal Action

What would the perfect version of this habit look like? (e.g., 60 minutes of focused writing)

2. The Default Action

What’s your standard expectation for this habit? (e.g., 30 minutes of writing)

3. The Minimum Viable Action

What’s the smallest version that still counts? (e.g., writing one paragraph)

On days when motivation is low, commit only to the Minimum Viable Action. This drastically lowers the activation energy required while maintaining consistency. Often, once you start with the minimum, you’ll continue to the default or even ideal action.

The Catalyst Identification Checklist

Use this checklist to identify potential catalysts that could lower activation energy for your specific goals:

- Social catalysts: Who could provide accountability, support, or motivation?

- Environmental catalysts: What changes to your surroundings would make starting easier?

- Technological catalysts: What apps, tools, or systems could reduce friction?

- Reward catalysts: What immediate positive reinforcement could you create?

- Knowledge catalysts: What information or skills would make the task less intimidating?

The Implementation Intention Formula

Research shows that creating specific implementation intentions dramatically increases follow-through. Use this formula:

Examples:

- “I will meditate for 5 minutes at 7:00 AM in my bedroom after brushing my teeth.”

- “I will write for 20 minutes at 8:30 PM at my desk after putting the kids to bed.”

- “I will exercise for 15 minutes at 12:30 PM in the living room after my lunch break.”

This formula eliminates decision-making in the moment, significantly reducing activation energy.

Conclusion: Making the Activation Energy Mental Model Work for You

The activation energy mental model is more than a tip for being productive. It’s a science-backed framework that helps us understand why starting is hard. It shows us how to make it easier.

It’s about building habits, finishing projects, or overcoming resistance. The trick is to find lower-energy starting points. This makes progress feel natural.

By reducing obstacles and adding catalysts, you create a space for growth. The Minimum Viable Action framework is a great tool for this. These strategies are based on science, not just tips.

Remember these key principles:

- Focus on reducing friction for positive habits and increasing friction for negative ones

- Use catalysts to lower activation thresholds for important activities

- Design your environment to support your goals

- Start with the smallest possible action to build momentum

- Create systems that make consistency easier than inconsistency

Willpower alone is rarely sufficient for lasting change. Instead, by intelligently designing your environment, habits, and systems to lower activation energy for positive behaviors, you can make progress almost inevitable.

What’s most important isn’t the size of your start. It’s that you start at all. Learning to overcome activation energy means taking that first step today.