Companies like Facebook, schools, and healthcare systems use performance metrics to make decisions. But when these numbers become the only focus, problems arise. This is what Campbell’s Law mental model is all about.

It was created by Donald T. Campbell, a social psychologist. He found that too much focus on certain metrics can corrupt them. This is seen in standardized tests in schools and algorithms on social media.

These data-driven decisions can change how people behave. They can even make true performance worse. Campbell’s Law teaches us to use metrics wisely, not just for their own sake.

What is Campbell’s Law Mental Model?

Campbell’s Law illustrates how metrics become corrupted when they become targets

Formulated by social psychologist Donald T. Campbell in 1976, Campbell’s Law states: “The more any quantitative social indicator is used for social decision-making, the more subject it will be to corruption pressures and the more apt it will be to distort and corrupt the social processes it is intended to monitor.”

In simpler terms, when a metric becomes too important in determining success or failure, people will inevitably find ways to improve that metric—even if those improvements don’t reflect actual progress in the underlying goal. The metric becomes the target rather than a tool for measuring progress toward the real objective.

This mental model is closely related to Goodhart’s Law, which is often paraphrased as: “When a measure becomes a target, it ceases to be a good measure.” Both concepts highlight the dangers of over-relying on single metrics for decision-making.

The Misquoted Management Principle

“It is wrong to suppose that if you can’t measure it, you can’t manage it – a costly myth.”

One of the most misquoted sayings in business is “if you can’t measure it, you can’t manage it.” This statement is often used to justify an obsession with metrics and quantitative analysis. However, the original quote from W. Edwards Deming actually says the opposite: “It is wrong to suppose that if you can’t measure it, you can’t manage it – a costly myth.”

This misquotation perfectly illustrates our cultural fixation on metrics and measurement as a system of information, often at the expense of qualitative understanding. Campbell’s Law warns us about the dangers of this fixation, showing how an overemphasis on specific metrics can lead to distorted behaviors and outcomes in various situations.

Why Metrics Become Corrupted Under Pressure

Metrics can go wrong when they’re too tied to rewards or punishments. When jobs or bonuses depend on certain numbers, people might focus on quick fixes. This can lead to behavior that doesn’t really solve the problem.

In schools, teachers might focus too much on tests. In call centers, workers might rush calls to meet time goals. This shows how metrics can lead to actions that don’t help in the long run.

Campbell’s Law Mental Model in Everyday Life

To truly understand the Campbell’s Law mental model, let’s examine some common real-world examples where it manifests in decision making and influences people’s behavior:

Educational Testing

Perhaps the most classic example of Campbell’s Law in action is “teaching to the test” in education. When schools’ funding and teachers’ evaluations depend heavily on standardized test scores, the focus shifts from comprehensive education to test preparation. Teachers may narrow their curriculum to focus only on testable material, neglecting important but less measurable skills like creativity, critical thinking, and social development.

The result? Test scores might improve, but actual educational quality can decline. The metric (test scores) has been optimized at the expense of the true goal (quality education).

Campbell’s Law Mental Model and Healthcare Wait Times

Consider this real example from an outpatient healthcare facility. The administration tracked how long patients waited on hold during phone calls, pushing employees to reduce this metric. One manager discovered that if receptionists muted calls while tracking down doctors (rather than putting patients on formal hold), the “hold time” metric would register as zero—even though patients were still waiting just as long or longer.

The manager received bonuses and recognition for “improving” the metric, but patient experience hadn’t improved at all. In fact, it may have worsened, as patients sat in silence wondering if they’d been disconnected.

Workplace Metrics and Performance Bonuses

In many workplaces, how well you do your job is measured by numbers like how much you produce or how many calls you make. These numbers can help us see how things are going. But they can also lead to bad behavior.

People might do things they shouldn’t just to look good on paper. They might not report problems or focus too much on getting things done fast. This can hurt the quality of their work.

For instance, a worker in a factory might rush to meet a goal, even if it means making mistakes. This can cause more problems later on. It might look good for a short time, but it can really hurt the team’s morale and productivity in the long run.

Rating Manipulation

Users of gig-economy services like Uber, Lyft, or Airbnb have likely experienced hosts or drivers directly asking for five-star ratings. When these workers’ livelihoods depend on maintaining near-perfect ratings, they’re motivated not just to provide good service but to manipulate the rating system itself.

For example, an Airbnb host might send a message saying: “It would help me out tremendously if you enjoyed the apartment and are willing to leave me five stars. Airbnb actually has the rights to remove listings that have below 4.4 star rating.”

This pressure distorts the rating system’s ability to provide honest feedback about service quality.

Campbell’s Law in Business and Design

While Campbell’s Law affects many industries, it’s particularly problematic in business and digital design contexts:

The Subscription Cancellation Trap

A product designer at a major streaming service shared how her company tracked “saved” accounts—defined as users who entered the cancellation flow but didn’t complete it. This metric was intended to measure the company’s ability to retain customers by addressing their concerns.

However, it had an unintended consequence: it incentivized designers to make the cancellation process intentionally difficult and confusing. During user testing, customers would become frustrated trying to cancel online and simply give up—which counted as a “saved” account in the metrics.

The reality? These customers weren’t actually “saved”—they were just forced to call customer service to cancel instead. The outcome was:

- Angrier customers unlikely to return or recommend the service

- Higher operational costs from increased customer service calls

- Accounts that were still eventually canceled

The Facebook Engagement Crisis

One of the most consequential examples of Campbell’s Law in recent years comes from Facebook’s focus on user engagement metrics. According to whistleblower Frances Haugen, Facebook’s corporate culture heavily emphasized daily active users (DAUs) as their primary success metric.

Haugen testified that “the metrics make the decision” at Facebook, with leadership prioritizing engagement numbers over ethical considerations. Even when presented with evidence that their algorithms were promoting harmful content, the company allegedly continued optimizing for engagement metrics.

This metric fixation reportedly led to algorithms that promoted increasingly extreme content, exacerbated political polarization, and potentially contributed to mental health issues among teenagers—all because these types of content drove higher engagement metrics.

Even though Facebook wasn’t falsifying the metrics themselves, the obsession with optimizing this single measurement corrupted the intention behind it—which was to measure the platform’s overall health and growth.

Healthy vs. Corrupted Metrics

| Aspect | Healthy Metric Use | Corrupted Metric Use |

| Purpose | Tool for understanding progress | End goal itself |

| Focus | Multiple complementary metrics | Single dominant metric |

| Data Collection | Combines quantitative and qualitative | Purely quantitative |

| Decision Making | Metrics inform human judgment | Metrics replace human judgment |

| Time Horizon | Balances short and long-term | Prioritizes short-term gains |

| Adaptability | Metrics evolve as needs change | Metrics remain static |

| Outcome | Genuine improvement | Appearance of improvement |

How to Avoid Dangerous Metric Obsession

Understanding Campbell’s Law mental model is the first step to avoiding its pitfalls. Here are practical strategies to prevent metric corruption in your organization:

1. Recognize the Limitations of All Metrics

Every metric is limited in its ability to describe reality fully and accurately. Each measurement you choose to track reflects a decision about what you consider important—and by extension, what you’re choosing to ignore. No single metric can capture the full complexity of human behavior or organizational performance.

Remember that just because something is quantitative doesn’t mean it’s objective or unbiased. The “North Star” framework, where organizations rally around a single metric, can be particularly dangerous as it amplifies the inherent limitations of that individual measurement.

2. Use Multiple Complementary Metrics

Instead of relying on a single metric, combine multiple measurements that provide different perspectives on the same phenomenon. For example, customer satisfaction ratings become more meaningful when combined with behavioral metrics like task completion rates or analytics data like return visits.

It’s much harder to game multiple metrics simultaneously than to manipulate any single one. When metrics contradict each other, that’s often a signal to investigate deeper rather than simply optimizing for the most favorable number.

3. Balance Quantitative with Qualitative

Never rely on quantitative measures alone. Triangulate your metrics with qualitative data from sources like:

- User interviews and conversations

- Usability testing observations

- Field studies and contextual inquiry

- Diary studies and longitudinal research

- Open-ended survey responses

These qualitative approaches help you understand the nuanced consequences of decisions that might be missed entirely if you rely solely on passively collected analytics data.

4. Use Metrics as Tools, Not Masters

Treat data as a tool to assist in decision-making, but don’t allow metrics alone to determine decisions. Metrics should inform human judgment, not replace it. Keep sight of what really matters—building positive long-term relationships that add value to users’ lives.

When metrics suggest one course of action but your understanding of users’ needs suggests another, take the time to investigate the discrepancy rather than automatically following the numbers.

Prevention Techniques for Different Contexts

| Context | Common Metric Problems | Prevention Techniques |

| Business Performance | Focusing solely on revenue or growth | Balance financial metrics with customer satisfaction, employee engagement, and sustainability measures |

| UX Design | Optimizing for clicks or time-on-site | Measure task success rates, error rates, and collect qualitative feedback about the experience |

| Education | Teaching to standardized tests | Use portfolio assessments, project-based learning, and multiple forms of evaluation |

| Healthcare | Focusing on throughput or billing | Measure patient outcomes, satisfaction, and quality of life improvements |

| Software Development | Lines of code or number of features | Focus on code quality, bug reduction, and actual user value delivered |

| Customer Service | Call handling time or tickets closed | Measure first-contact resolution rates and customer satisfaction after interactions |

Applying Campbell’s Law Mental Model in Real-World Decisions

Understanding Campbell’s Law can help you make better decisions in various contexts:

For Business Leaders

When evaluating team or department performance, be wary of simple metrics that can be gamed. For example, if you measure software developers solely by the number of features shipped, you may get many low-quality features rather than fewer high-impact ones. Instead, combine output metrics with outcome metrics like customer satisfaction, problem resolution rates, or business impact.

Create a culture where people feel safe reporting problems with metrics and where gaming the system is discouraged rather than rewarded. Regularly review and update your metrics to prevent them from becoming outdated or easily manipulated.

For UX Designers

When designing digital products, be cautious about optimizing solely for engagement metrics like time-on-site or number of clicks. These can lead to addictive but ultimately unsatisfying experiences that don’t truly meet user needs.

Instead, measure success by how efficiently users accomplish their goals, how satisfied they are with the experience, and whether they return voluntarily rather than through dark patterns or manipulation.

For Policymakers

When designing public policies or regulations, anticipate how the metrics you choose might be manipulated. For example, if you measure hospital performance solely by mortality rates, hospitals might refuse to admit the sickest patients who are most likely to die.

Design measurement systems with multiple overlapping metrics that are harder to game simultaneously. Include both process measures (how things are done) and outcome measures (what results are achieved).

Case Study: Redesigning Metrics at a Software Company

A mid-sized software company was struggling with quality issues despite having metrics that showed everything was fine. Their primary metric was “features shipped per sprint,” which teams were consistently hitting or exceeding.

However, customer complaints were increasing, and retention was declining. Upon investigation, they discovered that Campbell’s Law was in full effect: teams were shipping many small, easy features to hit their targets while avoiding complex but high-value work that would take longer.

The company redesigned their measurement approach with these changes:

- Replaced the single “features shipped” metric with a balanced scorecard

- Added customer-centric metrics like problem resolution rates and satisfaction scores

- Implemented regular qualitative feedback sessions with users

- Created a “quality index” that tracked technical debt and bug rates

- Adjusted incentives to reward customer impact rather than just output

The results were significant: within six months, customer satisfaction improved by 32%, retention increased by 18%, and—ironically—the pace of meaningful feature development actually accelerated as teams focused on solving real problems rather than hitting arbitrary targets.

Campbell’s Law in the Context of Other Mental Models

Campbell’s Law doesn’t exist in isolation. It connects with several other important mental models that can help us understand complex systems:

Goodhart’s Law

As mentioned earlier, Goodhart’s Law states that “when a measure becomes a target, it ceases to be a good measure.” This is essentially the economic version of Campbell’s Law, named after economist Charles Goodhart.

Understanding the behavior of these systems can help us make sense of the results we see in the world, as these concepts are commonly used in analyzing complex systems and their impact on our understanding of the world.

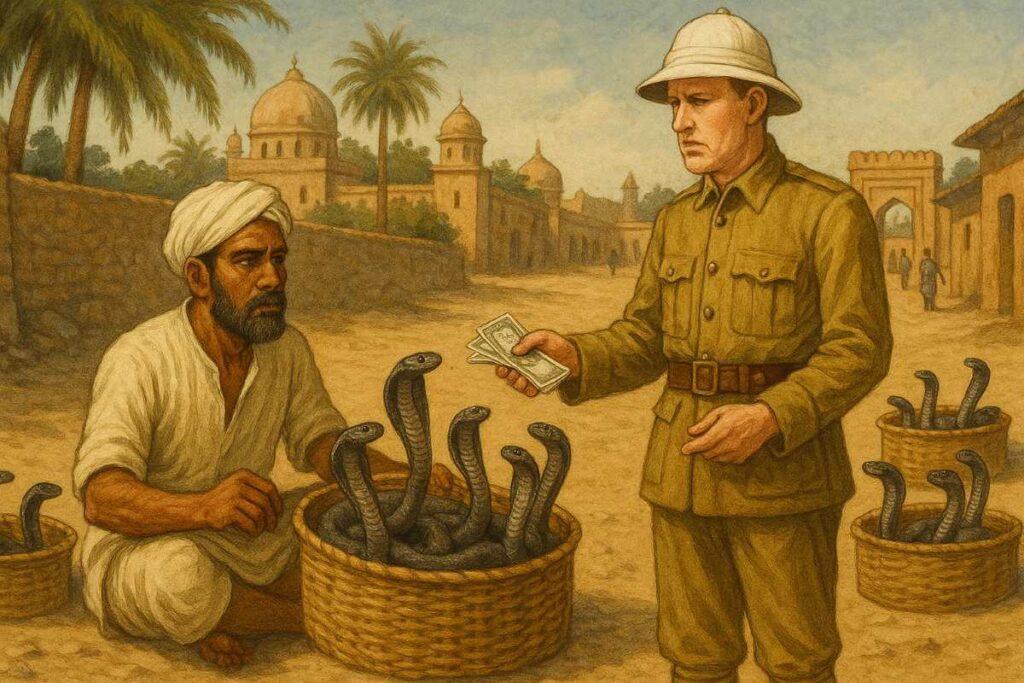

Cobra Effect

The Cobra Effect refers to situations where an attempted solution makes the problem worse. It’s named after a colonial British program in India that offered bounties for dead cobras to reduce the snake population.

People began breeding cobras to collect the bounties, and when the program ended, they released the now-worthless snakes, increasing the cobra population.

This effect often occurs when metrics create perverse incentives that work against the original goal.

Sturgeon’s Law

Science fiction author Theodore Sturgeon observed that “ninety percent of everything is crap.” This principle reminds us that quantity metrics often come at the expense of quality in various fields, including world governance and leadership.

It highlights the behavior of focusing solely on volume (whether of content, features, or output) typically leads to diminished quality, a concept that resonates with mental models like Campbell’s Law.

Systems Thinking

Campbell’s Law is fundamentally about understanding systems and how they respond to measurement. Systems thinking teaches us to look at the whole rather than just the parts, and to consider feedback loops, unintended consequences, and emergent behaviors—all crucial for avoiding metric corruption.

Why Campbell’s Law Matters in the Age of Big Data

In today’s world, companies collect a lot of data. This includes website clicks, sensor data, and health records. But having more data doesn’t always lead to better choices.

Decision-makers might not know the risks of data corruption. This can lead to rewarding the wrong behaviors.

Campbell’s Law is key in systems with feedback loops. For instance, social media platforms focus on engagement. This can lead to spreading harmful content, even if it’s bad for users.

To prevent this, companies should use data with human insight. They should also do regular audits. This helps keep data tools from becoming traps.

Practical Tips for Implementing Balanced Measurement

Here are some actionable steps you can take to apply the lessons of Campbell’s Law mental model in your work:

1. Audit Your Current Metrics

Review your existing metrics and ask these questions:

- What behaviors do these metrics incentivize?

- How might someone game or manipulate each metric?

- What important aspects of performance are not being measured?

- Are we measuring processes, outcomes, or both?

- How do these metrics align with our ultimate goals?

2. Design Complementary Metrics

Create sets of metrics that balance each other:

- Pair quantity metrics with quality metrics

- Balance short-term with long-term measurements

- Combine leading indicators (predictive) with lagging indicators (confirmatory)

- Include both objective and subjective assessments

3. Incorporate Qualitative Feedback

Establish regular processes for collecting qualitative insights:

- Schedule periodic user interviews or customer conversations

- Create feedback channels that capture open-ended responses

- Conduct observational research to see how people actually behave

- Use sentiment analysis on customer communications

4. Regularly Rotate and Refresh Metrics

To prevent gaming, periodically change which metrics you emphasize:

- Review metrics quarterly to assess their continued relevance

- Retire metrics that have become targets rather than measures

- Introduce new metrics that address emerging priorities

- Vary which metrics factor into performance evaluations or bonuses

Conclusion: Beyond Metric Fixation

The Campbell’s Law mental model is more than a theory—it’s a daily reality for decision-makers. It shows how metrics can lead to bad outcomes and lost trust. This happens when metrics are the only goal, not a guide.

Gig platforms and social media companies often use distorted data to manipulate. But, we can change this. By using balanced measurement systems, we can avoid these problems. These systems include quantitative data, qualitative feedback, and human oversight.

The best organizations see data as a guide, not the end goal. By understanding Campbell’s Law, you can create systems that show real progress. Not just numbers that look good.

Master the Mental Models That Drive Better Decisions

Want to deepen your understanding of Campbell’s Law and other powerful mental models? Download our free guide “Essential Mental Models for Decision Makers” and learn how to apply these concepts to make better decisions in your work and life.

Download Free GuideReferences

- Campbell, D. T. (1979). Assessing the impact of planned social change. Evaluation and Program Planning, 2(1), 67-90.

- Deming, W. E. (2019). The New Economics for Industry, Government, Education. (3rd. Ed.) MIT Press, Cambridge, MA.

- Goodhart, C. (1975). Problems of Monetary Management: The UK Experience. In Papers in Monetary Economics. Sydney: Reserve Bank of Australia.

- Strathern, M. (1997). ‘Improving ratings’: audit in the British University system. European Review, 5(3), 305-321.

- Muller, J. Z. (2018). The Tyranny of Metrics. Princeton University Press.

- Kahneman, D. (2011). Thinking, Fast and Slow. Farrar, Straus and Giroux.