By using Murphy’s Law, leaders in tech, finance, and healthcare can make better decisions. They can prepare for mistakes, avoid surprises, and create stronger systems. This approach helps them make more informed choices and build more reliable systems.

The Origins and Evolution of Murphy’s Law Mental Model

Edward Murphy examining aerospace equipment at Edwards Air Force Base, where Murphy’s Law was born

The origins of Murphy’s Law mental model trace back to the late 1940s at Edwards Air Force Base in California. Captain Edward A. Murphy Jr., an aerospace engineer, was working on the MX981 project – a rocket sled experiment designed to test human tolerance to extreme G-forces during rapid deceleration. During one particular test, strain gauges meant to measure these forces were installed incorrectly, rendering the collected data useless.

In his frustration, Murphy reportedly remarked something to the effect of, “If there’s any way to do it wrong, they’ll find it.” Dr. John Paul Stapp, the Air Force officer overseeing the project, later referenced this sentiment in a press conference when asked about their safety record. He attributed their success to their practice of always accounting for “Murphy’s Law” – the idea that if anything can go wrong, it will go wrong.

From these technical origins, Murphy’s Law mental model transcended the aerospace industry to become a widely recognized principle applicable to virtually every aspect of life. It evolved from a specific observation about human error in technical contexts to a broader philosophical principle about the inherent tendency of systems to fail and things to go awry. The concept resonates with our shared human experience of unexpected problems and setbacks, which explains its enduring popularity and relevance.

The Psychology Behind Murphy’s Law

Understanding these psychological underpinnings helps us appreciate why this mental model is so powerful and how we can leverage it constructively, especially during times when anything wrong seems likely. These experiences often resonate within a group, highlighting the universal nature of this phenomenon.

Negativity Bias: Why We Remember When Things Go Wrong

Humans possess an inherent negativity bias – we tend to register, process, and remember negative events more readily than positive ones. This evolutionary adaptation helped our ancestors survive by prioritizing potential threats. When something goes wrong, it creates a stronger neural imprint than when things go right, which is why we often feel that Murphy’s Law is constantly at work. We simply notice and remember the failures more vividly than the successes.

Risk Perception and Cognitive Biases

Our perception of risk is heavily influenced by cognitive biases. The availability heuristic causes us to overestimate the likelihood of events that come easily to mind – typically dramatic or emotionally charged events. Meanwhile, confirmation bias leads us to notice evidence that confirms our existing beliefs while overlooking contradictory information. These biases can make Murphy’s Law seem more prevalent than it actually is, as we selectively attend to instances that confirm the principle.

Paranoid Optimism: An Evolutionary Advantage

Evolutionary psychologists Martie Haselton and Daniel Nettle describe humans as “paranoid optimists.” This concept suggests that a tendency toward pessimism – assuming that things might go wrong – could have evolutionary benefits. Like an overly sensitive smoke detector, this bias might be wrong most of the time, but the benefits of being right even once (avoiding a catastrophic outcome) can be life-saving. Murphy’s Law, in this sense, represents a cognitive strategy that may have helped our ancestors survive by encouraging vigilance and preparation.

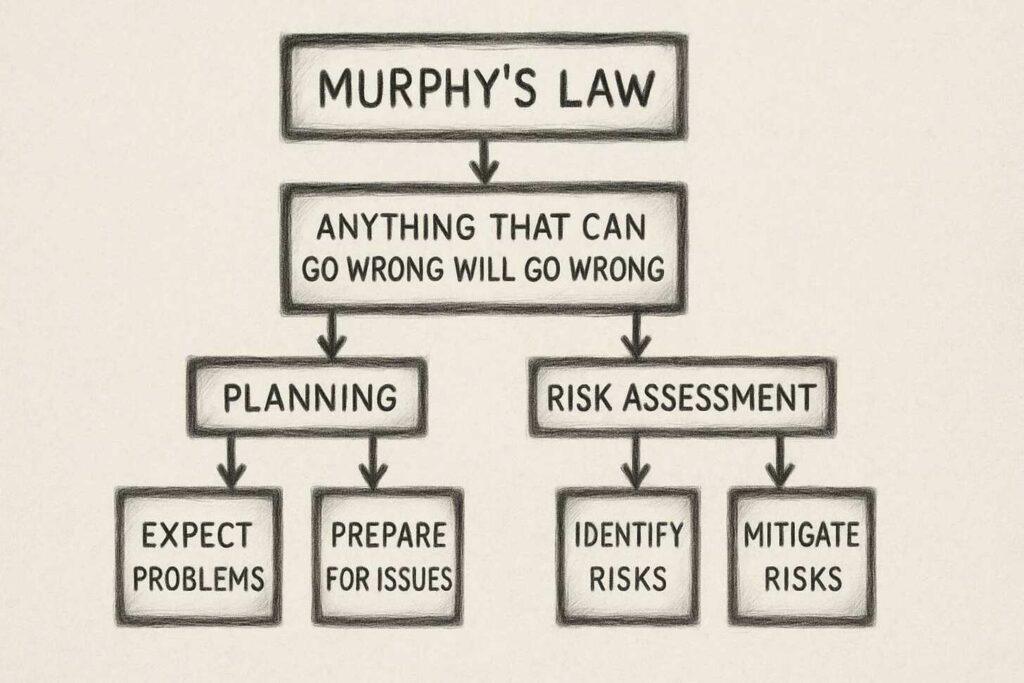

Murphy’s Law as a Mental Model for Decision-Making

From Pessimism to Preparedness

The true value of Murphy’s Law as a mental model lies not in pessimism but in preparedness. By anticipating that things might go wrong, we can take proactive steps to prevent problems or mitigate their impact. This shift in perspective transforms Murphy’s Law from a fatalistic observation into an actionable framework for risk management and contingency planning.

Core Components of the Murphy’s Law Mental Model

1. Potential Points of Failure

The first step in applying Murphy’s Law is identifying all the potential points where something could go wrong. This involves a systematic examination of processes, systems, or plans to uncover vulnerabilities.

2. Probability Assessment

Not all potential failures are equally likely. Assessing the probability of different failure scenarios helps prioritize where to focus preventive efforts and resources.

3. Impact Analysis

Beyond probability, it’s crucial to consider the potential impact or consequences of each failure. High-impact failures warrant more attention, even if they’re relatively unlikely.

4. Contingency Planning

Developing specific backup plans for the most critical and likely failure points ensures you’re prepared if things do go wrong, reducing reaction time and minimizing damage.

Practical Applications of Murphy’s Law

Murphy’s Law isn’t just a theoretical concept – it has practical applications across numerous domains. Let’s explore how this mental model can be applied in various contexts to improve outcomes and reduce the impact of unexpected problems.

Business and Project Management

For example, a software development team might anticipate potential technical challenges, team member absences, or integration issues with legacy systems. By identifying these risks early, they can implement code reviews, cross-train team members, and develop modular components that minimize the impact of individual failures.

Personal Finance and Investment

Murphy’s Law is particularly valuable in financial planning. The principle of diversification – not putting all your eggs in one basket – is a direct application of this mental model. By spreading investments across different asset classes, investors acknowledge that any single investment could underperform or fail.

Similarly, maintaining an emergency fund represents Murphy’s Law in action. By setting aside resources for unexpected expenses like medical bills, car repairs, or job loss, individuals build financial resilience against life’s inevitable curveballs.

Technology and System Design

In software development, rigorous testing aims to uncover bugs and vulnerabilities before products are released, acknowledging that errors are inevitable in complex code. Cybersecurity measures are similarly based on the principle that attacks will happen, and proactive defenses are necessary.

Personal Life and Relationships

Even in personal relationships, Murphy’s Law mental model can be a valuable framework. Anticipating potential misunderstandings and conflicts allows for more proactive and empathetic communication. Having strategies for conflict resolution ready before disagreements arise can help navigate the inevitable bumps in any relationship.

In daily life, applying Murphy’s Law might mean carrying a spare tire, keeping a first-aid kit at home, or having backup plans for important events. These small preparations can significantly reduce the impact of minor but annoying problems that are bound to occur.

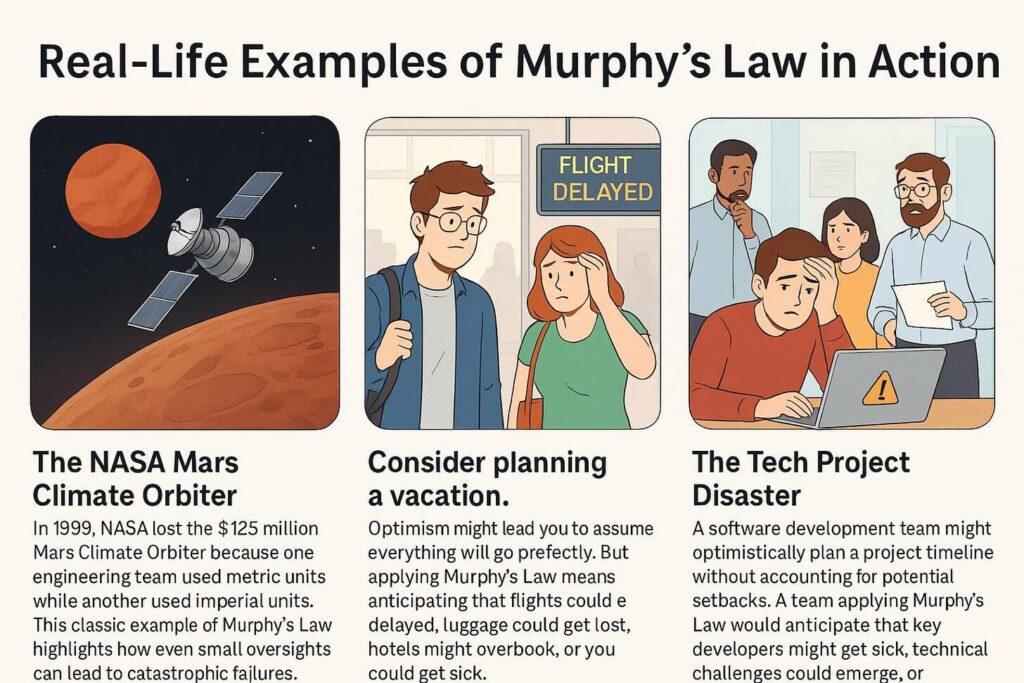

Real-Life Examples of Murphy’s Law mental model in Action

The NASA Mars Climate Orbiter

In 1999, NASA lost the $125 million Mars Climate Orbiter because one engineering team used metric units while another used imperial units. This classic example of Murphy’s Law highlights how even small oversights can lead to catastrophic failures. Organizations that apply the Murphy’s Law mental model implement rigorous verification processes and standardized protocols to catch such discrepancies before they cause problems.

The Travel Fiasco

Consider planning a vacation. Optimism might lead you to assume everything will go perfectly. But applying Murphy’s Law means anticipating that flights could be delayed, luggage could get lost, hotels might overbook, or you could get sick. Travelers who embrace this mental model purchase travel insurance, pack essential medications in carry-on bags, keep digital copies of important documents, and build buffer time into their itineraries.

The Tech Project Disaster

A software development team might optimistically plan a project timeline without accounting for potential setbacks. A team applying Murphy’s Law would anticipate that key developers might get sick, technical challenges could emerge, or requirements might change. They would build in buffer time, cross-train team members, and develop modular components that can be adjusted as needed, resulting in more reliable delivery despite inevitable challenges.

Limitations and Potential Misuses of Murphy’s Law

Benefits of Murphy’s Law

- Encourages proactive planning and risk mitigation

- Builds resilience through contingency planning

- Reduces the impact of unexpected problems

- Promotes thorough testing and verification

- Develops cognitive flexibility and adaptability

Limitations of Murphy’s Law

- Can lead to excessive pessimism and cynicism

- May cause paralysis by analysis if taken to extremes

- Can result in over-engineering and inefficiency

- Might be used to justify inaction or resistance to innovation

- Can create unnecessary anxiety about potential problems

While Murphy’s Law is a valuable mental model, it’s important to approach it with critical thinking and awareness of its limitations. Taken to an extreme, it can breed excessive pessimism and cynicism. If we constantly expect the worst in every situation, it can hinder creativity, risk-taking, and motivation.

Over-analyzing potential failure points can lead to “paralysis by analysis,” where we become so bogged down in planning that we fail to take decisive action. Similarly, applying Murphy’s Law excessively can result in over-engineering solutions, creating unnecessarily complex and costly systems when simpler approaches would suffice.

Perhaps most concerning is when Murphy’s Law mental model is misused as a justification for inaction or resistance to innovation. “Why try something new? It’s just going to go wrong anyway,” represents a cynical misinterpretation that contradicts the proactive spirit of this mental model.

Balancing Murphy’s Law with Optimism

The Growth Mindset Approach

Psychologist Carol Dweck‘s concept of the growth mindset offers a complementary perspective to Murphy’s Law. While Murphy’s Law encourages us to anticipate what might go wrong, a growth mindset frames setbacks as opportunities for learning and improvement rather than permanent failures. This combination – anticipating problems while viewing them as learning opportunities – creates a powerful framework for resilience and continuous improvement.

Practical Strategies for Balance

1. Prioritize Risks

Focus your preventive efforts on high-probability, high-impact risks rather than trying to anticipate every possible problem. This targeted approach prevents paralysis by analysis while addressing the most critical vulnerabilities.

2. Build in Flexibility

Rather than creating rigid plans that attempt to prevent all possible failures, develop flexible systems and processes that can adapt to unexpected challenges. This approach acknowledges that you can’t anticipate everything, but you can build resilience.

3. Celebrate Successes

Counteract negativity bias by intentionally noting and celebrating when things go right. This practice helps maintain motivation and perspective, preventing Murphy’s Law from becoming a self-fulfilling prophecy of pessimism.

4. Reframe Failures

When things do go wrong, view them as valuable data points rather than confirmations of Murphy’s Law. Ask: “What can we learn from this? How can we improve our systems or processes to prevent similar issues in the future?”

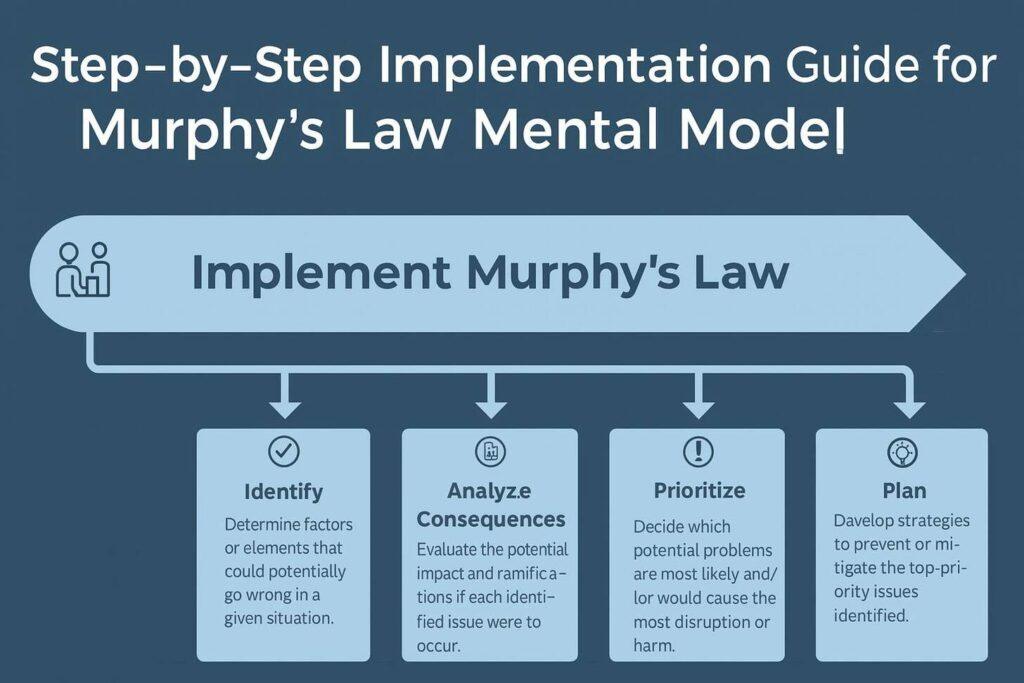

Implementing the Murphy’s Law Mental Model: A Practical Guide

Step 1: Identify Potential Points of Failure

Begin by brainstorming all the things that could go wrong in a specific situation – a project, plan, system, or even a simple task. Be comprehensive and think about each stage, component, or person involved. Ask yourself: “What are all the ways this could fail or deviate from the intended outcome?”

For example, if you’re planning a presentation, potential failure points could include technical glitches with your equipment, forgetting key points, running out of time, audience disengagement, or unexpected questions.

Step 2: Analyze the Consequences of Each Failure

For each potential failure point identified in Step 1, consider the consequences. How significant would the impact be if this problem actually occurred? Would it be a minor inconvenience, a moderate setback, or a major disaster? Categorize the potential consequences in terms of severity (e.g., low, medium, high impact).

Step 3: Prioritize Based on Impact and Probability

Not all potential problems are equally likely or equally impactful. Prioritize the failure points based on a combination of their potential impact (from Step 2) and their estimated probability of occurrence. Focus your attention and resources on addressing the high-impact and high-probability risks first.

| Risk Level | Low Probability | Medium Probability | High Probability |

| Low Impact | Lowest Priority | Low Priority | Medium Priority |

| Medium Impact | Low Priority | Medium Priority | High Priority |

| High Impact | Medium Priority | High Priority | Highest Priority |

Step 4: Develop Contingency Plans and Mitigation Strategies

For the prioritized failure points, develop specific contingency plans and mitigation strategies. What proactive steps can you take to prevent these problems from happening in the first place? And if they do occur, what backup plans can you put in place to minimize their impact and recover quickly?

Step 5: Test and Iterate

Whenever feasible, test your plans and systems to identify weaknesses and refine your mitigation strategies. For example, before a major project launch, conduct pilot tests or simulations to uncover potential problems in a controlled environment. After experiencing setbacks, learn from them and iterate on your plans and processes to become more resilient in the future.

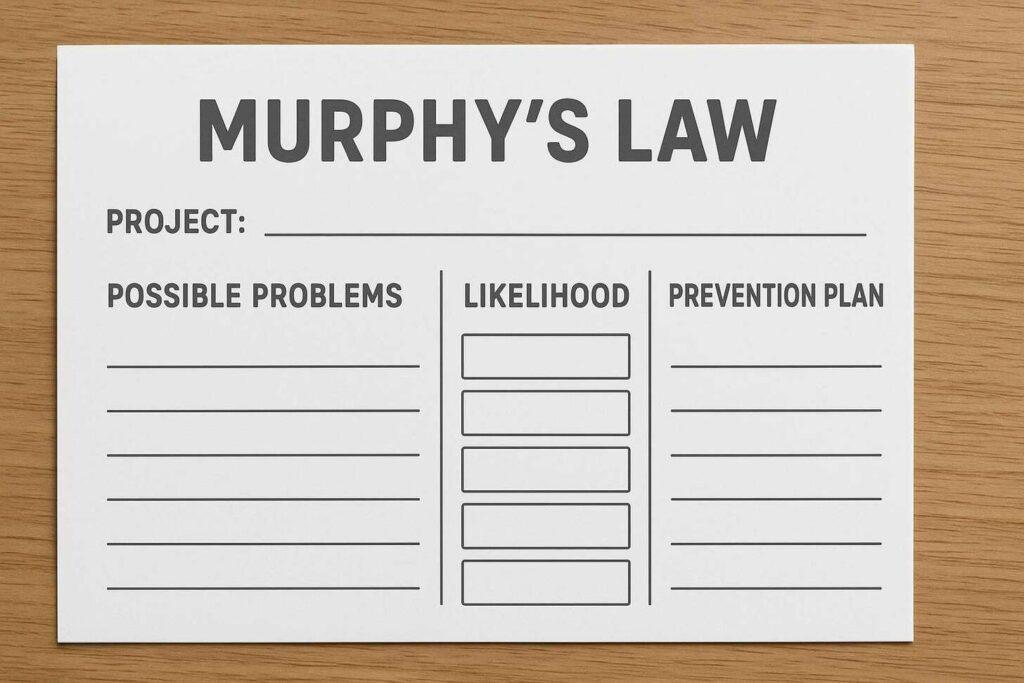

A Simple Thinking Exercise: Project Failure Anticipation

- Choose a current project or upcoming event

- List 3-5 key steps or components of the project

- For each step, identify at least one potential failure point

- Rate each failure’s impact and probability (low/medium/high)

- Develop a specific mitigation strategy or contingency plan for each

This exercise will help you internalize the process of applying Murphy’s Law and make it a more natural part of your thinking. With practice, this approach becomes less about pessimism and more about proactive preparation that actually increases your confidence and chances of success.

Frequently Asked Questions About Murphy’s Law

Is Murphy’s Law always negative and pessimistic?

No, Murphy’s Law itself is not inherently negative or pessimistic. While it acknowledges the potential for things to go wrong, its true value lies in its proactive and pragmatic nature. It’s about realism, not pessimism. By anticipating problems, we can take steps to mitigate them, ultimately leading to better outcomes. Think of Murphy’s Law as a “cosmic insurance policy” – it prepares you for the unexpected, not because you expect disaster, but because you want to be ready for anything.

Is believing in Murphy’s Law fatalistic?

No, believing in Murphy’s Law is not fatalistic. Fatalism implies a belief that all events are predetermined and inevitable, regardless of our actions. Murphy’s Law, in contrast, is about probability and the nature of complex systems. It suggests that in any complex endeavor, things can go wrong, and often will if we don’t take steps to prevent them. It’s an invitation to proactive action and preparation, not passive resignation.

How can I use Murphy’s Law without becoming overly pessimistic?

The key is to focus on the proactive aspect of Murphy’s Law. Use it as a tool for planning and problem-solving, not as a self-fulfilling prophecy of doom. Balance the anticipation of potential problems with a positive outlook and belief in your ability to overcome challenges. Murphy’s Law means preparing for the worst while still hoping and working for the best.

Don’t let it paralyze you with fear; let it empower you with foresight.

How does Murphy’s Law relate to other mental models?

Murphy’s Law complements several other mental models. It connects with the Precautionary Principle, which emphasizes taking preventive measures even in the absence of complete proof of risk. It relates to Second-Order Thinking by encouraging us to consider not just immediate actions but their potential consequences. The law also aligns with Hofstadter’s Law (“It always takes longer than you expect, even when you take Hofstadter’s Law into account”), which specifically addresses time estimation in projects. Using these models in combination provides a more robust approach to planning and decision-making.

Conclusion: Embracing Murphy’s Law as a Tool for Success

Murphy’s Law mental model turns pessimism into a powerful tool. It makes us ready for problems in any situation. This mindset helps us plan ahead and act quickly.

Leaders who use this model don’t focus on the worst-case scenario. They look for weaknesses, create backup plans, and handle issues efficiently. It helps in leading teams, managing money, or developing new tech.

In our unpredictable world, seeing risks ahead is key. Using Murphy’s Law boosts your confidence and ability to adapt. It leads to lasting success.