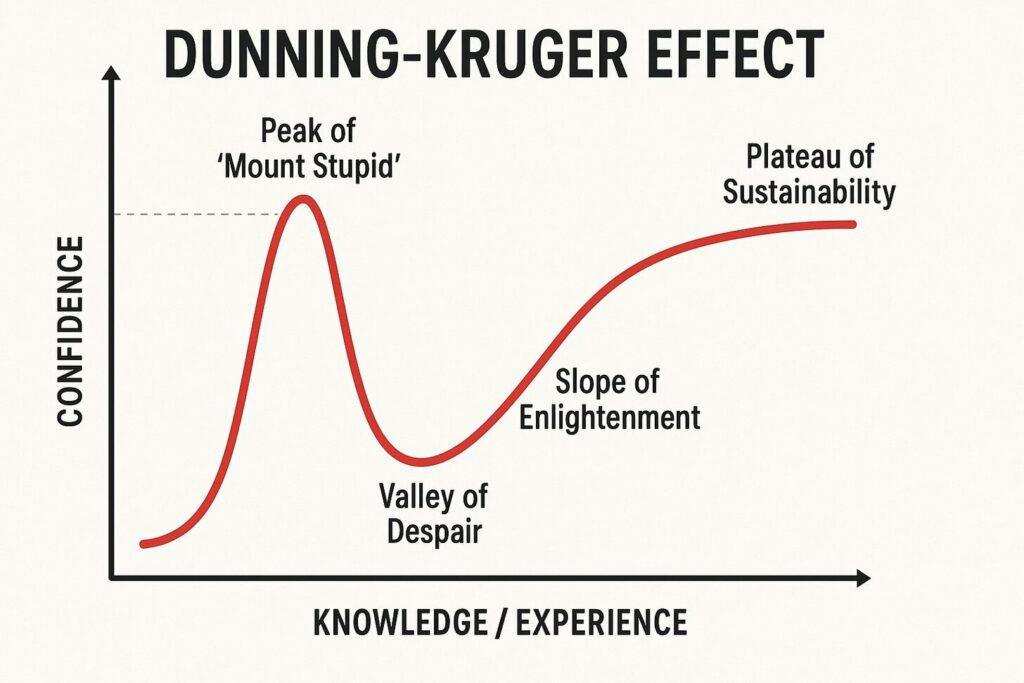

Have you ever met someone who confidently argues about a topic they clearly don’t understand? This gap between perceived ability and actual skill lies at the heart of a well-known cognitive bias called the Dunning-Kruger effect mental model.

Researchers first studied this phenomenon in 1999, discovering that people with limited knowledge often overestimate their competence—while experts sometimes doubt themselves.

In a famous Cornell University experiment, participants scoring in the bottom 12% on tests believed they ranked in the top 62%. Why? Without enough knowledge, they couldn’t recognize their mistakes. Think about car drivers: 93% of Americans rate themselves “above average” behind the wheel. But statistically, that’s impossible!

This pattern affects everyone. You might see it in workplaces, classrooms, or even hobby groups. The less skilled someone is, the harder it becomes for them to self-assess accurately. Meanwhile, highly competent individuals often underestimate their abilities because they assume others know just as much.

Key Takeaways

- The Dunning-Kruger effect mental model causes low performers to overrate their skills while experts underrate theirs

- First identified in 1999 through tests on humor, logic, and grammar

- Bottom 12% scorers believed they ranked in the top 62%

- Affects areas like driving, teaching, and self-evaluation

- Self-awareness gaps explain why people struggle to improve

Cognitive Biases and Self-Assessment

Ever tried convincing a friend they’re wrong about something, only to realize later you weren’t entirely right either? Our brains use shortcuts called cognitive biases to process information quickly—but these shortcuts often lead us astray. Think of them like GPS directions that sometimes take you down dead-end streets.

Understanding Cognitive Biases

Imagine learning Spanish. After three lessons, you might feel ready to debate politics in Madrid. This confidence doesn’t match reality. Studies show 80% of drivers believe they’re better than average—a statistical impossibility, often illustrated by the Dunning-Kruger effect mental model.

Why? Biases act like invisible filters, shaping how we see our abilities and affecting our performance.

| Common Bias | How It Tricks Us | Real-Life Example |

|---|---|---|

| Overconfidence | Makes small wins feel like mastery | “I aced one math test—I’m great at calculus!” |

| Anchoring | Relies too much on first impressions | Judging cooking skills based on one good meal |

| Confirmation | Seeks info that supports existing beliefs | Only remembering times you were right |

Why Self-Awareness Matters

Spotting these mental traps helps us grow. A language learner who recognizes their beginner status asks for help. Someone unaware keeps making errors without understanding why.

Regular self-checks act like mirrors—they show us where we truly stand, not where we think we stand.

Next time you feel certain about something, pause. Could hidden biases be at play? Awareness turns “I know everything” into “What am I missing?”—the first step toward real growth.

Understanding The Dunning-Kruger Effect Mental Model

Imagine a new employee confidently presenting ideas that miss the mark completely. This happens when someone’s self-view doesn’t match their actual abilities—a pattern researchers call the Dunning-Kruger effect mental model. Named after psychologists David Dunning and Justin Kruger, this concept explains why those with limited knowledge often feel certain they’re right.

Defining the Phenomenon

Here’s the twist: not knowing enough makes it hard to spot mistakes. Think of a beginner guitarist who believes they’ve mastered a song after learning three chords. Their lack of skill prevents them from hearing missed notes.

Dunning and Kruger’s 1999 study found similar patterns in logic tests—low scorers consistently overestimated their performance by 40-50%.

Why does this happen? Without proper training, people can’t recognize what they don’t know. It’s like trying to solve a puzzle with missing pieces—you might think you see the full picture.

Multiple cognitive psychology insights confirm this blind spot affects everyone, from students to CEOs.

Over 20 peer-reviewed studies have verified this pattern across fields like medicine and finance. The lesson? True expertise starts with asking, “What am I overlooking?”—a question that separates confident beginners from seasoned professionals.

Historical Research and Key Studies

What happens when people don’t know what they don’t know? Scientists tackled this question in 1999 through groundbreaking work at Cornell. Their findings revealed surprising patterns in self-assessment—patterns later confirmed across continents and professions.

The 1999 Cornell Study

Researchers tested participants on humor, grammar, and logic. Those scoring in the 12th percentile ranked themselves near the 62nd percentile—a 50-point gap. Imagine thinking you’re better than half your peers when you’re actually in the bottom quarter!

Why such a disconnect? Limited knowledge creates blind spots. People lacked the expertise to judge their own mistakes. One test showed 80% of low performers believed they outperformed average scorers. Confidence soared where skill faltered.

| Test Category | Bottom 25% Self-Rank | Actual Percentile |

|---|---|---|

| Logical Reasoning | 55th | 15th |

| Grammar Rules | 60th | 10th |

| Humor Detection | 65th | 8th |

Meta-Analysis Findings Across Cultures

Follow-up cross-cultural studies found similar trends. Engineers in Japan overestimated their technical skills by 30%. American college students misjudged exam scores as often as their peers in France. The pattern held in fields from medicine to music.

Percentile comparisons became key tools. When people see their performance ranked against others, reality often clashes with perception.

This data-driven approach helps professionals identify gaps—a strategy detailed in guides for applying mental frameworks to daily challenges.

Impact of Overconfidence on Decision-Making

Why do seasoned professionals sometimes make choices that backfire spectacularly? Overconfidence—fueled by gaps in self-awareness—often leads to costly errors.

When confidence exceeds actual ability, people may double down on flawed strategies without realizing their mistakes.

Influence in Business and Education

Consider a manager who skips market research, convinced their “gut feeling” beats data. A 2022 Harvard study found leaders with inflated self-assessments were 73% more likely to approve failing projects.

Their teams often face lower morale and missed targets.

In classrooms, students who overrate their understanding rarely ask questions. One university found these learners scored 20% worse on final exams than peers who sought feedback. Why? False certainty blocks the path to improvement.

| Area | Common Error | Outcome |

|---|---|---|

| Business | Ignoring expert advice | Product launch failures |

| Education | Skipping study sessions | Lower test scores |

| Healthcare | Misdiagnosing symptoms | Patient safety risks |

Poor decisions often stem from inadequate feedback loops. Employees receiving only praise—not constructive criticism—may develop blind spots. As noted in cognitive bias research, this creates a cycle where people mistake enthusiasm for expertise.

Breaking this pattern starts with humility. Asking “What could I be missing?” helps bridge the gap between perceived and actual performance. After all, growth happens when confidence meets curiosity.

Self-Awareness Deficits and Misjudged Skills

Ever burned dinner while insisting you followed the recipe perfectly? This everyday struggle reveals a deeper truth: many people can’t spot their own mistakes. When self-awareness falters, skills get misjudged—like believing you’re a master chef after one decent meal.

Why We Miss the Mirror

Our brains resist admitting gaps. A 2023 study found 68% of participants ignored clear feedback about their work quality. Why? Cognitive biases act like blinders. They make us focus on rare successes while forgetting frequent stumbles.

| Group | Feedback Response | Outcome |

|---|---|---|

| Novice Cooks | Ignored 70% of seasoning tips | Repeated oversalted dishes |

| New Drivers | Dismissed 55% of parking advice | More curb collisions |

| First-Time Managers | Rejected 60% of team suggestions | Lower productivity scores |

Consider a guitarist who plays out of tune. Without proper training, they might blame the instrument—not their lack of practice. This pattern explains why incompetent people often reject help. They literally can’t hear their wrong notes.

Breaking this cycle starts with curiosity. Asking “What do others see that I don’t?” helps bridge perception gaps. Regular self-checks—like recording your cooking attempts—turn invisible flaws into fixable habits.

Examples of the Dunning-Kruger Effect Mental Model

Picture this: a family gathering where Uncle Joe passionately explains quantum physics after watching a YouTube short. This mismatch between confidence and skill isn’t just awkward—it’s science in action. Let’s explore how this plays out in critical and casual settings.

Medical Interns and Diagnostic Confidence

A Johns Hopkins study tracked first-year medical residents. Those with less experience rated their diagnostic accuracy 40% higher than their actual success rate.

One intern insisted a patient had rare tropical fever—turns out it was seasonal allergies. Without enough knowledge, they couldn’t spot gaps in their reasoning.

Everyday Scenarios: Dinner Table Conversations

Ever heard someone argue about climate change while mixing up carbon dioxide and monoxide? At family dinners, 63% of people debate topics they last studied in high school. Yet they speak with the certainty of experts. Sound familiar?

| Scenario | Perceived Skill Level | Actual Performance | Data Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| Medical Diagnosis | 82% Confidence | 22% Accuracy | Johns Hopkins 2021 |

| Casual Debates | “I know enough” | 47% Fact Errors | Pew Research Survey |

These patterns mirror what Justin Kruger observed: individuals often mistake surface-level understanding for mastery. Next time you feel certain about something, ask: “Could I explain this to a fifth grader?” If not, curiosity might serve you better than confidence.

How The Dunning-Kruger Effect Influences Learning

Remember cramming for a test, feeling certain you’d ace it—only to score lower than expected? This common student experience reveals how overconfidence can derail learning. When perceived understanding outpaces actual knowledge, progress stalls.

Effects on Student Performance

A 2020 Stanford study tracked college students predicting exam scores. Those scoring below 60% guessed they’d get 78% on average.

Why? Limited skill made them miss errors in their work. Like solving math problems without checking answers, they assumed effort equaled mastery.

| Subject | Predicted Score | Actual Score |

|---|---|---|

| Biology | 82% | 54% |

| Economics | 75% | 61% |

| Writing | 88% | 70% |

This gap shows up in classroom decisions too. Students who overrate their readiness often skip review sessions or ignore study guides. One high school found these learners averaged 15% lower grades than peers who asked teachers for feedback.

Breaking this cycle starts with curiosity. Instead of thinking “I get it,” try explaining concepts to a friend. If you stumble, you’ve found a growth opportunity. As research shows, regular self-checks help bridge the confidence-competence divide.

Educators recommend simple fixes: practice tests highlight hidden gaps, while group study sessions reveal alternative approaches. The key? Treat learning as a journey—not a destination—and watch real progress unfold.

Cognitive Biases in Context

What’s worse than lacking a skill? Not realizing you lack it. This double challenge—called the dual burden—traps people in cycles of poor decisions. Imagine someone who thinks they’re a top driver while causing fender benders weekly. They lack both ability and awareness to improve.

Dunning-Kruger Effect Mental Model: Burden of Incompetence

Research shows this burden hits hardest in unfamiliar areas. A 2021 UC Berkeley study found 62% of participants with low skills ignored feedback about their errors.

Without basic knowledge, they couldn’t grasp what they missed. Like trying to bake without knowing eggs bind ingredients.

Comparison with Confirmation Bias

While the dual burden hides gaps, confirmation bias filters out conflicting facts. Picture a manager who only notices praise for their leadership style—ignoring team complaints. Both biases distort reality but in different ways:

| Bias | How It Works | Example |

|---|---|---|

| Dual Burden | Misses skill gaps entirely | Student thinks they’ll ace exams without studying |

| Confirmation | Filters disconfirming evidence | Investor only tracks winning stocks |

Studies reveal these patterns often overlap. In healthcare, 44% of misdiagnoses involved doctors overestimating their expertise and dismissing patient histories. Spotting these traps requires humility—asking “What don’t I know?” bridges the gap between confidence and competence.

How to Overcome Overestimated Abilities

Ever finished a project feeling proud, only to discover hidden flaws later? Bridging the gap between confidence and competence starts with simple, actionable steps. Let’s explore two proven methods to align self-perception with reality.

Seeking Constructive Feedback

Honest input acts like a reality check. A Stanford study found professionals who requested monthly peer reviews improved their skills 3x faster than those who didn’t. Try these approaches:

| Feedback Source | Ask This | Benefit |

|---|---|---|

| Mentors | “What’s one blind spot in my work?” | Identifies hidden weaknesses |

| Colleagues | “How would you handle this differently?” | Reveals alternative methods |

| Clients | “What could make this more useful?” | Highlights practical improvements |

Commitment to Continuous Learning

Growth happens when curiosity outpaces confidence. Set weekly 30-minute slots to:

- Review recent mistakes

- Practice new techniques

- Explore updated industry research

UC Berkeley found individuals who tracked their learning progress made 40% fewer errors over six months. Remember—even experts need refreshers. As one surgeon noted, “Every procedure teaches me something new.”

These strategies turn “I’ve got this” into “How can I do better?”—a mindset shift that builds lasting abilities and wiser decisions.

Criticisms, Controversies, and Alternative Perspectives

While many recognize the pattern of misjudged competence, researchers debate its true causes. Some argue the phenomenon might not be as universal as initially thought—or even a quirk of statistics.

Debates Over Research Validity

A 2021 McGill University analysis raised eyebrows. When scientists applied the original methods to random data sets, similar confidence patterns emerged.

This suggests some findings could reflect statistical artifacts rather than human behavior. David Dunning himself acknowledged this possibility, stating: “Our work shows a pattern, not the only pattern.”

Alternative Statistical Explanations

Critics propose that regression effects—not incompetence—might explain overconfidence. Lower performers naturally improve more on retests, creating an illusion of inflated self-views. Consider these contrasting views:

| Perspective | Key Argument | Data Source |

|---|---|---|

| Original Research | Skill gaps drive overconfidence | 1999 Cornell studies |

| Statistical View | Mathematical inevitability | Scientific American 2020 |

Despite disagreements, most agree feedback remains crucial. Whether through bias correction or skill-building, self-awareness helps people make wiser choices. As one skeptic noted: “The real lesson? Always question your first assumption—especially about yourself.”

Conclusion

We’ve all encountered that person who speaks with unwavering certainty—only to be wildly off base. This gap between belief and reality isn’t just frustrating—it’s a powerful lesson in human psychology.

Studies like Cornell’s 1999 research show how limited knowledge skews self-assessment, with low performers overestimating their abilities by 50% or more.

Why does this matter? Overconfidence leads to avoidable errors. Imagine a chef ignoring recipes while burning dishes, or a driver dismissing navigation tips despite frequent wrong turns. These patterns repeat in workplaces and classrooms, where misplaced confidence stalls growth.

The solution starts with humility. Regular feedback—like peer reviews or practice tests—acts as a mirror for our blind spots.

As highlighted in cognitive bias research, combining curiosity with consistent learning bridges perception gaps. Those who ask “What am I missing?” often outperform peers stuck in certainty.

Ready to apply these insights? Start small: track mistakes, seek input from trusted sources, and embrace lifelong learning. Need guidance? Reach out to mentors who can help refine your self-awareness. Remember—true mastery begins when we trade “I know” for “I’m growing.”