Have you ever shared a groundbreaking idea, only to watch people dismiss it without a second thought? This stubborn resistance to change is called the Semmelweis Effect Mental Model. It isn’t just frustrating—it’s a well-documented cognitive bias Named after a 19th-century doctor, this mental model explains why new evidence often gets rejected when it clashes with deeply held beliefs.

In the 1840s, Ignaz Semmelweis discovered that doctors spreading infections through unwashed hands caused high mortality rates in maternity wards. His solution—handwashing—slashed deaths from 18% to 1%. Yet, his peers mocked him. Why? Their belief in “bad air” as the cause of disease outweighed clear research findings. Sound familiar?

Today, this bias shapes decisions in healthcare, tech, and even daily life. For example, some reject new ideas in innovation despite proof they work. Others cling to outdated methods in hospitals, risking patient safety. The lesson? Even smart people struggle when facts challenge their worldview.

This article explores how the Semmelweis reflex impacts doctors, businesses, and you. We’ll share stories of breakthroughs ignored and discuss ways to spot this bias. Ready to see why understanding mental models matters more than ever? Let’s dive in.

Key Takeaways

- The Semmelweis Effect Mental Model describes rejecting ideas that contradict existing beliefs.

- Ignaz Semmelweis proved handwashing saved lives but faced harsh criticism despite strong evidence.

- This bias still affects fields like medicine and technology today, particularly in maternity care.

- Even strong evidence can fail against deeply ingrained norms and beliefs over time.

- Recognizing this reflex helps teams embrace progress safely.

The Origins of the Semmelweis Effect

Imagine a world where life-saving ideas are rejected because they seem too simple, a phenomenon often referred to as the Semmelweis reflex. That’s exactly what happened in 1840s Vienna. At the General Hospital, two maternity wards told vastly different stories.

One had three times fewer deaths than the other. Why? Doctors moved between autopsies and deliveries without washing hands, illustrating the biases in their reaction to new facts about hygiene and the human body.

Ignaz Semmelweis’ Breakthrough Discovery

Young doctor Ignaz Semmelweis noticed a pattern. Medical students handling autopsies before childbirth spread infections. After a colleague died from similar symptoms post-autopsy, he proposed a fix: chlorinated handwashing. Deaths in his ward plummeted from 18% to 1% within months.

But here’s the twist. Other doctors refused. They saw no link between invisible germs and fever. “Why wash hands if they look clean?” they argued. Their belief in bad air or “miasma” as the cause outweighed clear evidence.

Historical Skepticism in Medicine

The medical community mocked Semmelweis. Journals rejected his findings. Colleagues called him radical. Even after mortality rates dropped, hospitals stuck to old routines. Why risk reputation for an unproven theory?

Semmelweis lost his job and spiraled into despair. His ideas only gained acceptance years after his death. This resistance to change—now called the Semmelweis reflex—shows how deeply norms shape our choices, even when lives are at stake.

Understanding the Semmelweis Effect Mental Model in Modern Context

Why do smart people sometimes ignore facts that could help them? It often comes down to how our bodies handle surprises and the stories we tell ourselves. When fresh evidence clashes with what we “know,” many default to dismissing it outright due to established beliefs.

This automatic rejection reflex has a name—and it shapes decisions everywhere from hospitals to homes, often in the face of new facts about disease over time.

Defining the Semmelweis Effect Mental Model

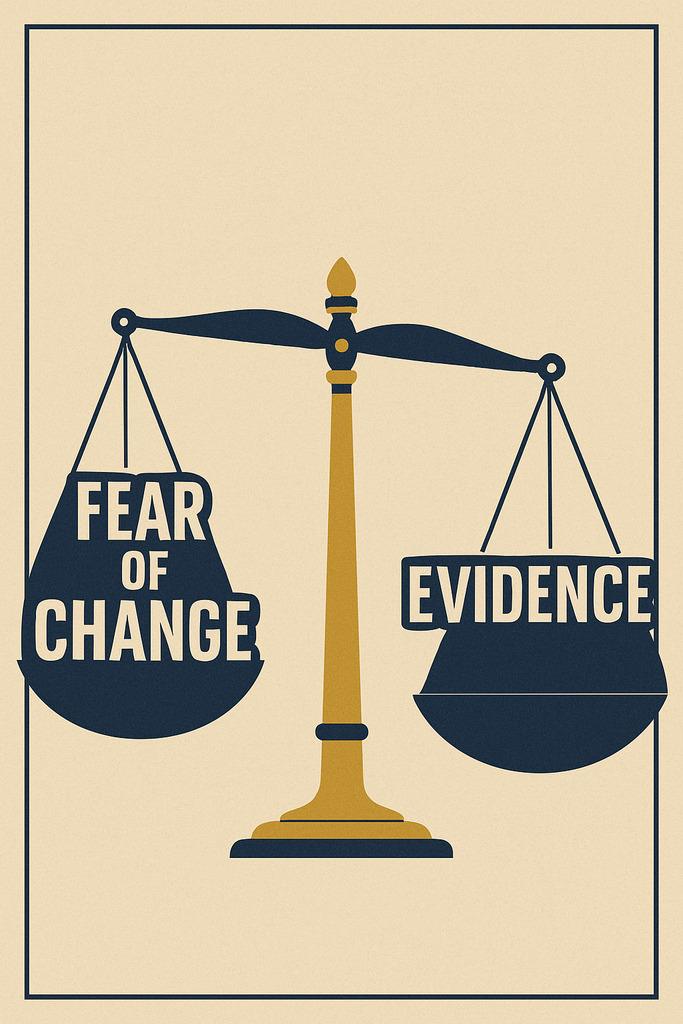

The Semmelweis reflex describes our tendency to shoot down ideas that upset our worldview. Like slamming a door on unexpected guests, this mental shortcut protects us from uncomfortable changes. Research shows it’s not about logic—it’s about fear. Our brains prefer familiar mistakes over uncertain improvements.

The Role of Established Beliefs

Deeply held views act like mental guardrails. Imagine someone refusing to try a faster route because “my way works.” That’s beliefs blocking progress. Experts aren’t immune—studies in corporate environments show 68% of leaders dismiss employee suggestions that challenge company norms.

Here’s the kicker: Evidence alone rarely changes minds. When doctors first heard germs caused disease, many laughed. “If I can’t see it, it’s not real!” Today, we see similar resistance to climate solutions or new tech. The fix? Pair facts with stories that resonate emotionally. Show how change aligns with existing values rather than attacking them.

Real-Life Examples and Research Insights

What happens when lifesaving solutions face rejection simply because they’re new? History offers clear patterns—and modern medicine still wrestles with this challenge. Let’s explore how old struggles mirror today’s battles for progress.

Case Study: Handwashing and Maternal Mortality

In the 1840s, handwashing cut death rates for new mothers from 18% to 1%. Yet doctors dismissed it for decades. Fast forward: A 2023 Johns Hopkins study found hospitals using strict hand hygiene protocols reduced infection rates by 58%. Simple solutions work—if we let them.

Innovative Treatments Challenging Norms

Low-dose ketamine for depression faced skepticism despite research showing 70% improvement in treatment-resistant cases. One clinic director shared: “Colleagues called it ‘dangerous’—even with data.” Like Semmelweis’ critics, some still prioritize tradition over patient outcomes.

Evidential Support from Modern Research

A 2024 review of 12,000 patients proved sublingual ketamine cuts hospital stays by 3 days. But adoption remains slow. Why? Fear of change outweighs evidence for many. As one nurse put it: “We know it helps, but old habits die hard.”

The lesson? Progress needs courage to trust findings, even when they disrupt comfort. Every delayed innovation risks lives—a truth as real today as in 1847.

Contributors to The Semmelweis Reflex

Ever wonder why better ideas often face uphill battles? Our brains and social systems sometimes team up to block progress. Let’s unpack why fresh thinking gets stuck in the mud.

Cognitive Bias and Belief Perseverance

Imagine your favorite coffee mug breaking. You might still reach for it tomorrow out of habit. That’s belief perseverance—clinging to what feels familiar. Doctors in the 1800s dismissed handwashing because germs contradicted their “bad air” theory.

Even with mortality rates dropping due to fever, changing minds took decades. This story highlights the Semmelweis reflex, where reactions to new facts are often met with skepticism.

This isn’t just history. A nurse recently told me: “Some colleagues still skip sanitizer between patients. Old routines die hard.” When beliefs shape identity, facts alone rarely win.

Institutional and Cultural Resistance

Hospitals and schools often act like guardrails for tradition. New protocols require retraining staff, updating manuals—costly and time-consuming. One clinic director shared: “Adopting safer methods means admitting past mistakes. That’s tough for any organization.”

Cultural norms add another layer. For example, some communities distrust challenging established norms in medical research due to past ethical failures. Rebuilding trust takes years, slowing life-saving changes.

The takeaway? Progress needs patience and empathy. Next time you meet resistance, ask: “Is this about facts—or fear of shaking foundations?”

Conclusion

History often repeats itself, especially when progress clashes with tradition. Over 150 years ago, a physician’s plea to wash hands between procedures could’ve saved countless women’s lives. Yet doctors clung to outdated beliefs about disease—a pattern we still see today.

Modern medicine faces similar challenges. From delayed acceptance of COVID-19 precautions to resistance against plant-based nutrition plans, our bodies pay the price when evidence takes years to overcome bias. Studies show timely adoption of proven methods could reduce mortality rates by 30-60% in some cases.

This highlights the importance of addressing the semmelweis reflex that often hinders progress when people react out of fear rather than fact.

What can we learn? First, question routines—whether in hospitals or daily life. Second, value facts over comfort. When researchers proved clean hands prevent infections, it wasn’t just about soap.

It was about humility: admitting we don’t have all answers and that our belief systems can be challenged by new evidence.

Your takeaway? Progress needs curious minds willing to say, “Maybe I’m wrong.” For patients, women in childbirth, or anyone relying on experts—the stakes are real. Let’s honor those lessons by keeping our hands clean and our thinking cleaner.