Have you ever read a news article that felt too balanced to be truthful? That’s the heart of the Okrent Law Mental Model. Created by Daniel Okrent, a journalist and editor at Time and The New York Times, this idea challenges how we view fairness in media. It argues that striving for “balance” can sometimes hide the real story.

Daniel Okrent isn’t just a media pioneer. He also invented fantasy baseball! But his sharp insights into journalism left a bigger mark. In 1999, he gave a famous lecture predicting the end of print media.

He warned that clinging to old habits—like forced neutrality—could hurt trust in news. This tendency to favor balance can be a problem in the field of journalism, especially when reporting on significant events.

Think about climate change debates. If a report gives equal space to scientists and skeptics, does that really reflect reality? Okrent’s model shows how this “balance” can mislead.

It’s not about picking sides—it’s about showing truth clearly, even if it feels uneven. This is a critical point in understanding the theory behind the fallacy of balance in media reporting.

Key Takeaways

- The Okrent Law Mental Model reveals how overemphasizing balance can distort facts.

- Daniel Okrent highlighted the tendency to present facts in a way that can mislead people.

- His 1999 lecture predicted print media’s decline and critiqued outdated reporting norms.

- Forced neutrality in topics like science or politics often creates false equivalencies.

- This mental model helps readers spot when “fairness” might be hiding deeper truths

Introduction to the Okrent Law Mental Model

Have you ever bought a car because the salesperson made both options sound equally good? That’s how the balance fallacy works. It’s the tendency to present opposing views as equally valid, even when facts don’t support it.

This idea shapes how we process information at work, home, and in the media, creating an opportunity to question the actions behind each part of the narrative. In this field, movements toward understanding the fact that balance can mislead are crucial.

Understanding The Okrent Law Mental Model

Imagine two coworkers arguing about a project deadline. One wants it done fast, the other wants perfection. A manager might split the difference to seem fair. But what if rushing creates errors?

The world often rewards compromise—even when it hides better solutions. This tendency to overlook the problem can lead to significant issues in decision-making.

This happens in news too. A climate story might give skeptics equal airtime despite overwhelming scientific consensus.

Our place in society—like our job or beliefs—can make us prefer “balanced” takes over messy truths. For example, in this country, people often prioritize the appearance of fairness over the knowledge of actual events, leading to a distorted view of reality.

Why It Matters Today

Social media amplifies extreme opinions. One viral post denying vaccines might get shared as much as expert advice. This tendency to oversimplify complex issues creates a fallacy that can mislead the public. People crave simplicity, but reality isn’t always 50/50.

Ask yourself: when did you last hear a fringe view presented like mainstream fact? For example, in this country, many things are presented as balanced, yet they overlook critical events.

At work, this model helps teams spot false compromises. Should you cut costs or improve quality? Sometimes, the middle ground isn’t the answer. By questioning forced balance, we make room for smarter choices in a complex world.

The Origins of The Okrent Law Mental Model

What does it take to redefine fairness in journalism? For decades, newsrooms clung to rigid ideas of balance—until one editor asked: “At what cost?” The answer came from a man who’d shaped media at America’s most iconic publications.

Daniel Okrent’s Background

Born in 1948, this Detroit native didn’t follow typical paths. After studying at Michigan University, he joined Time magazine in 1980.

There, he pioneered “people-centric” storytelling—making complex issues relatable through human angles, a key tendency in journalism that highlights the human experience in every place and case.

His boldest move came in 1999. As the first public editor at The New York Times, he challenged reporters to question their biases. “Neutrality isn’t about giving equal time,” he argued. “It’s about giving accurate time.”

This point exemplifies the ongoing problem in the world of journalism where the fallacy of forced balance often overshadows the truth.

From Time and New York Journalism

At both Time and the Times, Daniel Okrent saw how forced balance distorted truth. During the 2004 election, he criticized coverage that treated factual claims and opinions as equally valid. His famous lecture that year warned: “Print media will die if we keep pretending all views deserve equal weight.”

| Publication | Role | Key Contribution |

|---|---|---|

| Time Magazine | Managing Editor | Introduced narrative-driven reporting |

| The New York Times | Public Editor | Created accountability standards |

| Sports Illustrated | Columnist | Invented fantasy baseball (1980) |

Ever notice how weather reports don’t debate whether rain exists? Okrent pushed journalists to treat settled facts—like climate science—with similar clarity. His career shows how deep experience in New York’s media trenches can spark ideas that reshape entire industries.

Defining Mental Models

How does your brain make sense of traffic patterns or predict tomorrow’s weather? We use mental models—simplified versions of reality that help us navigate complex situations. As Charlie Munger said, “You’ve got to have models in your head… and you’ve got to use them routinely.”

The Basics of Mental Representations

Think of these models as tools for your mind. A chef uses recipes (a type of theory) to break cooking into steps. Similarly, we turn messy problems into clear steps, enhancing our ability to tackle each challenge.

Psychologist Philip Johnson-Laird showed how people use these frameworks to test ideas through “what-if” scenarios that can name potential outcomes.

Here’s the key difference: mental models aren’t pictures in your head. Imagery shows how something looks. Models explain why things work at a fundamental level.

Imagine a car engine—you might visualize it (imagery) but need a model to understand fuel combustion in order to see how each part functions.

| Aspect | Mental Model | Mental Imagery |

|---|---|---|

| Purpose | Explain systems | Visualize objects |

| Complexity | Simplifies problems | Shows details |

| Example | Supply/demand theory | Picture of a market |

The Role in Human Reasoning

These models shine—and stumble—in daily life. They help you decide which grocery line moves fastest. But they can also create fallacies, like assuming “balance” always means fairness.

Ever packed an umbrella just because the forecast said “50% chance”? That’s a model in action—sometimes overly cautious!

Curious how to apply these frameworks beyond theory? Notice when you automatically predict outcomes. Did your shortcut help… or hide better solutions?

Okrent Law Mental Model and the Pursuit of Balance

Ever trusted a news story because it showed “both sides”—only to realize later one wasn’t based on facts? This is the objectivity paradox: trying to be fair can accidentally spread misinformation.

Imagine a debate where 99 doctors say masks work, but one disagrees. This tendency to balance can mislead people. Giving them equal airtime distorts reality.

The Hidden Cost of 50/50 Reporting

Some things aren’t up for debate. We don’t argue if the moon exists—we show photos. Yet media often treats settled science or historical facts as open questions. A famous analysis by Daniel Okrent once noted: “Not every issue has two equal sides. Sometimes, there’s just what’s true.”

Think about health myths. If a TV segment gives equal point to experts and anti-vaccine voices, viewers might think both are equally valid. But data shows vaccines save lives. This tendency to balance here becomes a dangerous problem.

Countries face this too. When a country’s leaders deny climate disasters despite evidence, journalists feel pressured to “balance” their coverage. But this creates false doubt.

Remember the 1969 moon landing? Some outlets still report conspiracy theories as if they’re plausible, despite the overwhelming evidence presented in New York.

Have you spotted this in your life? Maybe a work meeting where bad ideas got equal time to good ones. The point isn’t to silence views—it’s to weigh them against facts. After all, some things aren’t opinions. They’re just reality.

Critical Thinking and Decision-Making

Ever made a split-second choice that backfired—then wished you’d slowed down? Our brains love shortcuts, but complex business decisions demand deeper thinking. Let’s explore how to shift from snap judgments to clear-eyed analysis.

From Intuition to Analytical Reasoning

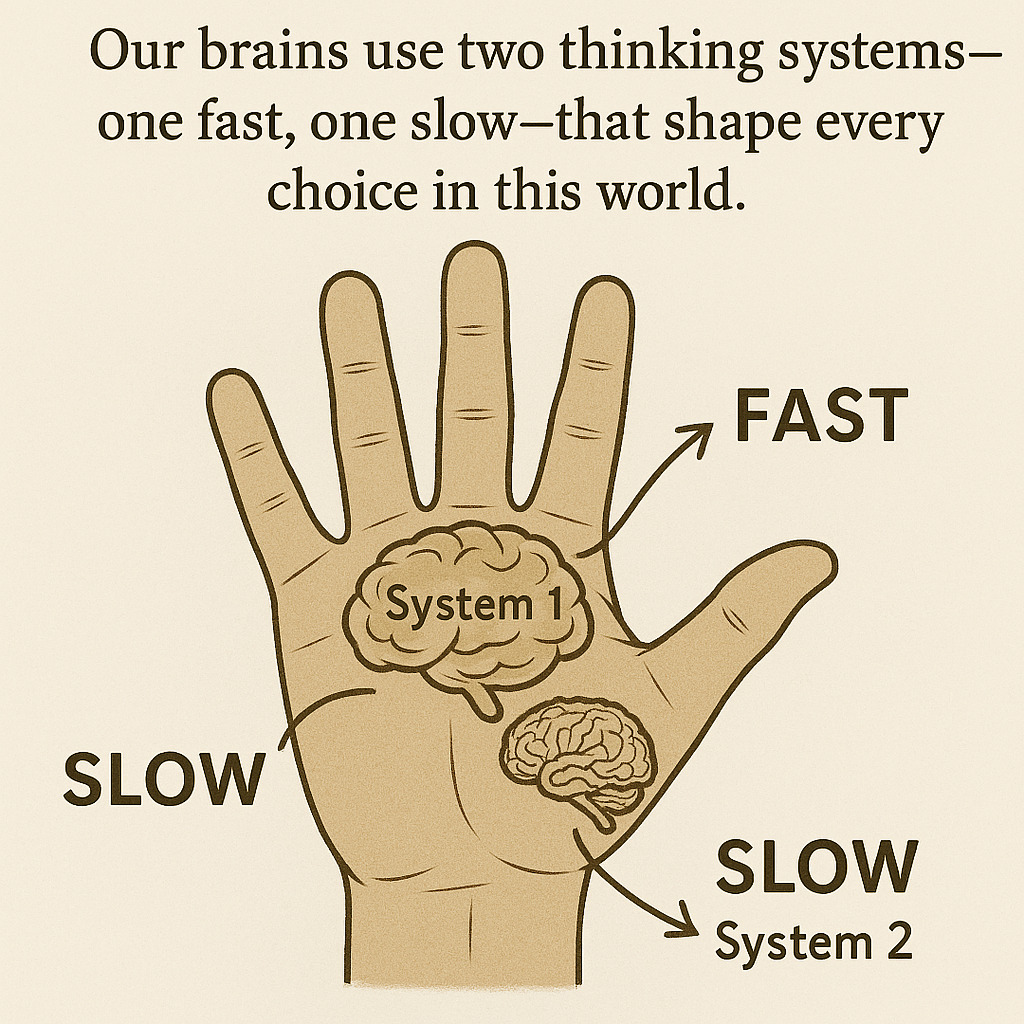

Psychologist Daniel Kahneman described two thinking systems. System 1 acts fast—like trusting a familiar brand. System 2 digs deeper, asking: “Does this case really need that premium service?”

| System 1 (Intuition) | System 2 (Analysis) | |

|---|---|---|

| Speed | Instant | Minutes to hours |

| Energy Use | Low | High |

| Best For | Routine tasks | High-stakes choices |

Last year, I nearly signed a client because their pitch felt right. But checking their financials revealed red flags. My gut said “yes”—analysis said “run.”

Consider a case study from tech: When major business events forced layoffs, one company used data to cut costs without firing staff. They analyzed which roles boosted revenue—saving jobs while staying profitable.

Next time you face a tough call, ask: “Am I reacting… or really thinking?” Your best decisions often come from pressing pause.

Influence of Mental Models in Daily Life

How often do you pause to think about why you trust a certain brand or take a specific route home in a bustling place like New York? Our brains use shortcuts—like mental blueprints—to navigate countless choices. These frameworks form the invisible rules behind everyday decisions that people make.

Consider crossing a busy street. You glance left, then right—using past knowledge to judge safety. This split-second habit is a mental model in action. Similarly, when buying coffee, you might choose the same shop daily.

Why? Past positive experiences form a trust pattern your brain relies on, illustrating a tendency to stick with familiar options despite the potential for better choices.

| Situation | Model Used | Outcome |

|---|---|---|

| Choosing a job | “Stability over risk” | Missed creative opportunities |

| Grocery shopping | “Stick to the list” | Avoided impulse buys |

| Investing savings | “Diversify portfolios” | Reduced financial risk |

Here’s a twist: A man I know always bought Brand X tools because “they last forever.” But when a friend recommended Brand Y, he refused. Later, he discovered Brand Y’s drill was lighter and cheaper. His loyalty model hid better options.

Simple models help us manage chaos. Imagine planning a trip without using maps or reviews! Yet clinging too tightly can blind us. Ever followed a recipe exactly, only to realize swapping spices improved the dish?

Building knowledge about these patterns changes everything. Notice when you default to “how it’s always done.” Could a tweak lead to better results? What models is that man in the mirror using… without even knowing?

Contextualizing Mental Models in Journalism

What if your morning newspaper could predict the future? For decades, journalists used mental frameworks that assumed print would always dominate. These invisible rules shaped everything from story selection to ad placement—until reality forced a rewrite.

Lessons Learned from Print Media’s Evolution

In the 1990s, newsrooms operated under a “paper-first” model. Stories were written for physical layouts. Ads funded local reporting. This system worked… until the internet changed the level of competition overnight.

| Aspect | Traditional Journalism | Digital Journalism |

|---|---|---|

| Focus | Daily editions | 24/7 updates |

| Speed | Next-day reporting | Real-time alerts |

| Engagement | Letters to editor | Social media comments |

| Revenue | Print ads | Click-based models |

Print’s decline taught harsh lessons. Papers that stuck to old models folded. Others adapted—like The Washington Post, which invested in online subscriptions.

Their success hinged on the ability to rethink what news delivery could be, an example of how the industry can evolve in any country.

Today’s challenge? Avoiding digital-era balance traps. When every tweet gets treated as breaking news, how do we maintain journalistic standards? The real question isn’t about platforms—it’s about preserving truth-telling ability amid chaos, a problem that reflects a tendency to prioritize speed over accuracy in the news.

Could your local paper become an AI-powered app? Maybe. But without human level judgment, even smart algorithms can’t replace seasoned reporters asking the right question, as highlighted by the theory proposed by Daniel Okrent in New York.

Exploring Psychological Insights

Ever wonder why people sometimes make decisions that don’t make sense later? Our brains use two thinking systems—one fast, one slow—that shape every choice in this world. Let’s unpack how these systems work and why spotting their quirks matters in any country.

Fast vs. Slow Thinking

Daniel Kahneman’s research shows our minds switch between two modes. System 1 acts instantly—like catching a falling cup. System 2 kicks in when solving math problems or planning budgets. Both are useful, but mixing them up causes trouble.

| System 1 | System 2 | |

|---|---|---|

| Speed | Lightning-fast | Slow & steady |

| Energy | Low effort | High focus |

| Use Case | Daily habits | Complex choices |

Biases That Trick Us

Philip Johnson-Laird found we often fall for mental traps that people in various countries experience. Here are common ones:

- Confirmation bias: Only noticing facts that match what we already believe, a tendency that can skew our perception of events

- Anchoring effect: Relying too much on the first number we hear, an example of how our decision-making can be influenced

Ever bought a car because the salesperson named a high price first? That’s anchoring in actions. Or trusted a news source just because it agreed with you? Classic confirmation bias, illustrating the way we form opinions based on limited information.

Recognizing these patterns is part of smarter thinking. Next time you’re stuck, ask: “Am I using System 1 shortcuts… or really analyzing?” Your best actions start with knowing the difference, which is crucial for problem-solving at any level.

The Impact on Business and Economics

Ever passed up a job offer to start your own business? That’s opportunity cost in action—the hidden price of every choice we make. In the field of economics, these invisible trade-offs shape how companies grow, compete, and sometimes disappear.

Opportunity Costs and Creative Destruction

Imagine a bakery deciding between buying new ovens or hiring staff. Choosing ovens means losing the movement toward better customer service. Economist Joseph Schumpeter called this “creative destruction”—when innovation wipes out old systems to create new value.

| Traditional Approach | Innovative Approach | Outcome |

|---|---|---|

| Sticking with typewriters | Adopting computers | Lost market share |

| Manual bookkeeping | Using cloud software | Faster decisions |

| Local store only | E-commerce expansion | Broader reach |

Look at the auto industry. Horse carriage makers vanished when cars arrived. But this order of change sparked entire new fields—like traffic lights and gas stations.

Today’s tech shifts follow the same pattern: streaming services replaced DVD rentals, creating jobs in digital content, a case study of how people adapt in a changing world.

How does this affect you? Next time you face a big decision at work, ask: “What’s the true cost of saying yes?”

Your best movement forward might require leaving old habits behind—just like businesses in New York that thrive by rewriting their order of priorities, an example of how the law of innovation works in every country.

Social and Cultural Implications

Have you ever chosen a school for your child based on what “everyone says” is best? Our shared beliefs—like invisible rules—shape how societies grow and change. From neighborhood traditions to global movements, mental frameworks quietly steer collective choices.

How Mental Models Shape Our Worldview

Cultural studies show how groups of people develop shared shortcuts. During the civil rights era, many saw protests as disruptive—until leaders reframed them as moral imperatives.

This shift in understanding turned a movement into a catalyst for nationwide change, influencing how we view the world.

Rigid frameworks can also blind us. In the 1990s, companies dismissed remote work as unproductive, a fallacy that limited their ability to adapt.

That mental model hid opportunities for flexibility—until COVID-19 proved otherwise. Today, hybrid work reshapes cities and family routines, challenging the way we think about work as a part of our lives.

| Past Event | Dominant Model | New Insight |

|---|---|---|

| Industrial Revolution | “Factory work = progress” | Environmental costs emerged |

| 2008 Financial Crisis | “Markets self-correct” | Systemic risks ignored |

| #MeToo Era | “Keep workplace issues private” | Collective voices create change |

Ever noticed how opportunities get missed when we cling to “how things are”? Like when strategies must adapt to shifting inequalities. Our mental maps need updates—just like GPS recalculates when roads close.

What current debates might future generations question? Whether discussing AI ethics or climate policies, our shared understanding today writes tomorrow’s history. Are we framing issues in ways that help… or limit progress?

Unpacking Common Reasoning Fallacies

Have you ever believed two opposing ideas could both be true? That’s the trap of reasoning fallacies—errors in logic that twist facts. These mistakes matter because they shape choices in work, relationships, and even public policy. In the world of reasoning, people often face the problem of conflicting viewpoints, and this tendency can lead to confusion.

Take the “on the one hand” fallacy. Imagine a debate about homework. One parent says: “On one hand, it teaches responsibility. On the other, it stresses kids.” Sounds balanced, right?

But if studies show homework doesn’t boost grades, pretending both sides are equal hides the fact. This situation reflects a broader tendency in society where the name of balance can obscure the real issues at hand.

Fallacies thrive when we skip context. A news clip might say: “Some say masks work, others call them useless.” If 95% of scientists agree masks help, this “balance” misleads.

It’s like arguing seatbelts aren’t needed because one person survived a crash without them. This highlights the importance of understanding the level of evidence behind claims.

How to spot shaky claims? Check the elements:

- Does the source have expertise?

- Are stats from peer-reviewed studies?

- What’s missing from the argument?

Last week, I saw a post claiming “coffee causes cancer.” Digging deeper, the study cited tested rats given 50 cups daily! Context changes everything. Now, I ask: “What elements of this fact are being left out?”

Next time you hear “both sides,” pause. Ask: “Is this actually a 50/50 split… or just clever framing?” Truth isn’t always in the middle—it’s where the evidence points.

Understanding these dynamics is crucial in navigating the complex web of arguments that people encounter in everyday discussions.

Interdisciplinary Perspectives on Mental Models

Why do some ideas stick across centuries while others fade? The answer lies in how different fields shape our thoughts. From tax codes to tech ethics, frameworks from economics, psychology, and philosophy quietly steer our collective choices.

Insights from Economics, Psychology, and Philosophy

Adam Smith once wrote: “It is not from the benevolence of the butcher that we expect our dinner, but from his regard to his own interest.”

This economic principle—self-interest driving markets—shows how models influence government policies. Think tax laws designed to encourage business growth.

Psychology adds another layer. Studies show people cling to familiar ideas, even when facts shift. Ever resisted a new app because “the old one works fine”? That’s loss aversion bias—a mental shortcut shaping both personal thoughts and corporate strategies.

Philosophers like Descartes asked: “How do we know what’s true?” His famous “I think, therefore I am” became a bedrock for rationalism. Today, this framework informs debates about AI ethics. Should machines follow human moral laws… or develop their own?

Consider pandemic responses. Governments balanced economic models (protect jobs) with public health research (save lives). The “right” choice depended on which lens leaders used. How often do you blend logic and gut feelings when deciding?

Next time you face a tough call, ask: “Which invisible rules am I following?” The best decisions often mix structured thinking with creative leaps. After all, even Einstein needed philosophy to frame his physics breakthroughs!

The Okrent Law Mental Model

The Okrent law mental model: “The pursuit of balance can create false equivalency”.

What happens when companies ignore clear warnings to maintain the status quo? History is filled with moments where the pursuit of “balance” clouded judgment—often with costly results.

Let’s explore how misplaced fairness shaped critical decisions and what we can learn.

Real Examples from History and Business

In the 1950s, tobacco companies funded studies questioning smoking’s health risks. By giving equal weight to a handful of dissenting scientists, they created false doubt for decades.

This resistance to overwhelming medical truth delayed public health reforms—a stark lesson in skewed balance.

Consider Blockbuster’s collapse. As streaming emerged, executives dismissed it as a niche trend. Their resistance to digital shifts—rooted in loyalty to physical rentals—left them bankrupt by 2010. Meanwhile, Netflix embraced change, rewriting entertainment rules.

| Industry | Outdated Approach | Updated Approach | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|

| Journalism | Print-only focus | Digital-first strategy | Survived media shifts |

| Retail | Ignoring e-commerce | Omnichannel sales | Boosted revenue 300% |

| Energy | Denying climate data | Investing in renewables | Won investor trust |

Daniel Okrent’s 1999 lecture warned: “Neutrality isn’t splitting differences—it’s spotlighting facts.” He cited cases where editors buried lead stories to avoid “taking sides,” letting critical truths go unnoticed. His insights remind us: progress often means choosing clarity over comfort.

Ever faced a similar crossroads at work? Maybe clinging to old processes while competitors innovate. Okrent’s lecture urges us to ask: “Are we balancing views… or burying reality?” The best decisions honor evidence—even when it disrupts tradition.

Enhancing Workplace Decision-Making

Imagine your team of people spending hours debating solutions but still picks the wrong path. Sound familiar? Workplace choices often hinge on hidden patterns—mental shortcuts we use daily in this world.

By mapping these frameworks, teams can cut through the noise and act smarter in a way that aligns with Daniel Okrent’s theories.

Strategies for Smarter Choices

Start by naming the models your organization relies on. Do your meetings default to “majority rules” even when experts disagree? Try the “weighted vote” method. Give specialists 2 votes on topics they know best. This simple tweak balances fairness with expertise.

| Traditional Approach | Model-Based Strategy | Result |

|---|---|---|

| First-come-first-served task assignments | Skills matrix matching | 25% faster project completion |

| Annual budget reviews | Rolling quarterly forecasts | 18% cost reduction |

| Generic safety protocols | Role-specific risk assessments | 41% fewer workplace incidents |

A tech company redesigned its hiring using the “comparative advantage” model. Instead of seeking perfect candidates, they focused on job tasks where applicants excelled most.

New hires’ productivity jumped 30% in six months, a testament to Daniel Okrent’s theory of optimizing people’s strengths in the workplace.

Safety practices show models in action. Factories using “pre-mortem analysis” (imagining failures before they happen) report 60% fewer accidents.

Teams ask: “What could go wrong?” then build safeguards to address potential problems. This proactive approach is the way forward in the world of workplace safety.

Could your organization benefit from clearer frameworks? Next time your team debates, try this: List everyone’s assumptions. Test them against data.

You might find that “how we’ve always done it” isn’t the best path for your job—or your workers’ safety.

Learn From Economic and Strategic Theories

Why do some businesses thrive while others struggle with simple choices? The answer often lies in economic frameworks that shape smart strategies. Let’s explore how timeless ideas like comparative advantage and transaction costs guide modern companies.

Applying Comparative Advantage and Transaction Costs

David Ricardo’s 1817 theory of comparative advantage isn’t just for nations trading wine and cloth. Imagine a tech startup deciding whether to build software in-house or partner with experts.

By focusing on what they do best—product design—they outsource coding to specialists. This “trade” lets both sides win through efficiency.

Transaction cost theory explains why firms make or buy components. When Apple started designing its own chips, they reduced reliance on suppliers.

Though costly upfront, it gave control over quality and timelines. As economist Oliver Williamson noted: “Companies grow by minimizing the friction of doing business.”

| Strategy | Traditional Approach | Model-Based Approach |

|---|---|---|

| Manufacturing | Make all parts | Outsource non-core items |

| Marketing | Generic campaigns | Data-driven targeting |

| Expansion | Open new offices | Remote teams + hubs |

Case Studies in Modern Business

During COVID, a local bakery switched from wholesale to direct delivery. Using comparative advantage, they focused on signature pastries while partnering with a logistics app for transport. Sales jumped 40% despite lockdowns.

Look at Amazon’s 2021 decision to bring shipping in-house. By cutting third-party transaction costs, they now control 67% of their U.S. deliveries. This shift mirrors Schumpeter’s “creative destruction”—replacing old systems with better solutions.

Next time you face a tough choice at work, ask: “What would Ricardo do?” Economic theories aren’t just for articles—they’re tools to build smarter, faster-growing businesses. How could your team use these models today?

Policy, Governance and The Broader Impact

Have you ever noticed how traffic lights seem to “know” when to change? Behind every public system lies invisible rules that shape our daily lives. These mental frameworks quietly guide everything from city planning to national laws, often without us realizing it.

How Mental Models Inform Public Decision-Making

In 1933, the U.S. government launched the New Deal using an economic model called Keynesian theory. Leaders believed spending could boost jobs during the Depression—a radical idea at the time. This understanding reshaped America’s government role in crises.

Today’s climate policies show similar patterns. When the EU set strict emission targets, they relied on scientific models predicting environmental movements. Critics called it extreme, but data showed the truth: bold action was needed.

| Historical Policy | Guiding Model | Outcome |

|---|---|---|

| Medicare (1965) | “Shared risk” healthcare | Covered 19M seniors |

| No Child Left Behind (2001) | Standardized testing theory | Mixed academic results |

| Paris Agreement (2016) | Climate projection models | 35% emissions cut by 2030 |

Media plays a key role too. During COVID, some outlets framed mask rules as “freedom vs. safety.” This fallacy ignored public health knowledge, turning a health problem into political drama.

What case studies teach us? When Detroit redesigned bus routes using rider data (not old maps), commutes got 22% faster. Good government means updating thoughts as facts change.

Next local election, ask: “What invisible rules shape these policies?” Spotting mental models helps us push for smarter laws—not just familiar ones.

Conclusion

Our journey through information fairness reveals a powerful truth: balance doesn’t always equal truth. Daniel Okrent’s framework shows how equal airtime can distort reality when facts aren’t split 50/50.

Like giving flat-Earthers equal debate time with astronauts, this tendency risks misleading audiences in media, work, and daily choices. In New York, people often face this problem when trying to navigate the complex law of information dissemination.

Mental shortcuts shape everything from news consumption to team decisions. Johnson-Laird’s research reminds us these patterns simplify complex issues—but can also hide better solutions.

Ever stuck to a flawed process because “that’s how we’ve always done it”? That’s the trap in action, a common point of contention in many places.

Here’s the key takeaway: Question first, balance second. When facing conflicting claims, ask: “What’s the evidence ratio?” If 95% of experts agree on climate science, giving 5% equal space misrepresents reality.

This applies to office debates too—not all opinions deserve equal weight, especially when considering the theory behind what constitutes valid arguments.

Final reflection: When did you last accept a “balanced” report that felt off? Next time, dig deeper. Scrutinize sources. Weigh consensus against outliers. Truth often lies not in the middle, but where the data points, reflecting the many things we must consider.

Ready to see the world through sharper lenses? Start noticing the invisible frameworks guiding your choices. Sometimes, the fairest approach is letting facts speak louder than forced neutrality, a crucial form of engagement in today’s society.