Ever wondered why a star athlete’s record-breaking game often fades into mediocrity? Or why that lucky slot machine win feels like a streak you can’t sustain?

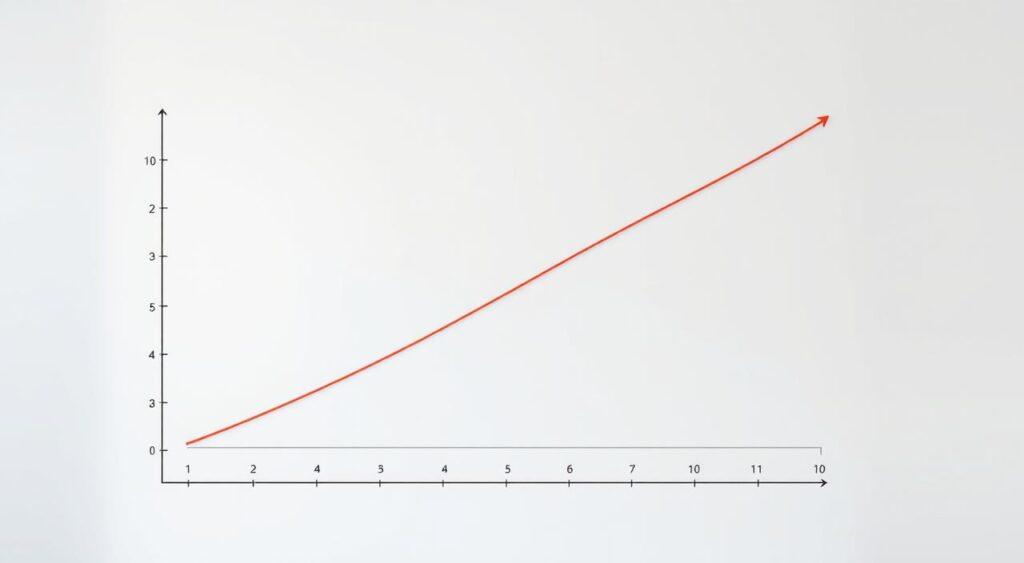

The answer lies in the regression to the mean, a statistical phenomenon shaping everything from sports to stock markets. This concept explains why extreme results—whether stellar or terrible—tend to balance out over time.

For instance, a software team that fixes a record 100 bugs in one week will likely see fewer the next, not because they slacked, but because extremes naturally retreat toward averages1.

Even a sales team praised after a record month might simply be regressing to their usual performance, not because the praise “worked.”

Key Takeaways

- Regression to the mean describes how extreme outcomes naturally shift toward average results over time.

- It explains why “hot streaks” in sports or business often cool down1.

- Misreading this phenomenon can lead to wrong conclusions, like crediting praise for a team’s recovery when it was just statistical balancing2.

- Understanding it helps avoid costly errors in decision-making across careers and personal goals.

- It’s a core statistical principle affecting everything from parenting to investing strategies.

Think of it as life’s way of evening the odds. This model helps you see past misleading extremes and make smarter choices—whether evaluating a stock’s rise or a child’s test scores. Let’s break down how this works and why it matters in your world.

Understanding Regression to the Mean

Imagine you scored way above average on a test. Chances are your next score will be closer to the middle. That’s statistical regression in action. It’s a core statistics terminology concept showing extreme results tend to even out over time3. Let’s break it down.

What does it really mean? When something extreme happens—like a company’s stock soaring—it often drops back toward its usual level. This isn’t magic; it’s math. Extreme events usually mix luck and skill, and luck rarely stays consistent4.

For example, a baseball player hitting a career-high batting average one season will likely drop slightly the next year. That’s regression to the mean.

History in action: Sir Francis Galton first noticed this in the 1800s. He saw that tall parents had kids shorter than them, while short parents had kids taller than them4. Today, this idea is vital for statistical inference.

Businesses use it to avoid overreacting to sudden sales spikes or drops. Doctors see it when patients feel better after a treatment simply because their symptoms were an extreme case3.

Key takeaways:

- Extreme results often fade because luck plays a role

- Used in medicine, sports, and finance to avoid false conclusions

- Galton’s work shows it’s a natural part of data patterns

Recognizing this principle helps you spot when a trend is real or just a statistical fluke. Stay curious—your decisions will thank you later.

Examples of Regression to the Mean

Regression to the mean isn’t just a theory—it’s a pattern found in everyday life. It shapes decisions in sports, schools, and health care.

Sports Performance

Elite athletes often face the “Sports Illustrated cover curse.” Stars featured on the magazine’s cover after a record-breaking season usually underperform the next year3. This isn’t bad luck but regression to their true skill level.

Managers praised for four straight wins might just be benefiting from a lucky streak5. Data science reveals that rookie baseball stars often face a “sophomore slump” as their performance aligns with their long-term averages3.

Academic Grades

Ever wonder why top students’s scores dip on retakes? Random guessing on a 100-question test averages 50%—so top scorers naturally regress toward that mean3.

Massachusetts schools saw improved test scores after being labeled “underperforming,” but this was often regression, not better teaching3.

Health Outcomes

Hospital infection spikes often drop the next month, tempting staff to blame new protocols. But this could just be regression to the mean5. Overreacting by prescribing more antibiotics wastes resources—data science helps avoid costly misjudgments3.

Hospital infection spikes often drop the next month, tempting staff to blame new protocols. But this could just be regression to the mean5. Overreacting by prescribing more antibiotics wastes resources—data science helps avoid costly misjudgments3.

Elite athletes often face the “Sports Illustrated cover curse.” Players featured on the cover after extraordinary seasons usually return to average performance, not due to a curse but statistical regression3.

Similar to this, managers with four consecutive wins might just be riding luck, not skill5. Baseball rookies often face a “sophomore slump” as their stats align with their true ability3.

Ever wonder why top student’s scores dip on retakes? Random guessing on a 100-item test averages 50%—so high scorers regress toward that mean3. Massachusetts schools labeled “underperforming” often improved next year, but this was often regression, not policy changes3.

Hospital infection spikes often drop the next month, tempting staff to blame new protocols. But this could just be regression to the mean5. Overreacting by prescribing more antibiotics wastes resources—data science helps avoid costly misjudgments3.

Examples of Regression to the Mean

Regression to the mean isn’t just a theory—it’s a hidden pattern shaping decisions in sports, schools, and hospitals. Here’s how it plays out in real life:

Sports Performance

Top athletes often face the “Sports Illustrated cover curse.” Stars featured on the magazine’s cover after a record-breaking season usually underperform the next year3. This isn’t a curse but a return to their average ability.

Managers praised for four straight wins might just be riding luck, not skill5. Rookie baseball stars often face a “sophomore slump” as their performance aligns with their true ability3

Academic Grades

Students who guess randomly on a 100-question test average 50%—so top scorers usually drop to closer to that mark on retakes3. Schools labeled “underperforming” often improve the next year, but this is often regression to the mean, not policy changes3.

Health Outcomes

Health metrics can fluctuate wildly. A hospital’s infection spike might drop the next month, but this could be regression to the mean, not treatment success5.

Data science helps avoid costly overreactions, like overprescribing antibiotics for temporary spikes3.

How to Identify Regression to the Mean

Spotting regression to the mean starts with careful observation. Let’s break down how to apply this concept practically using statistical analysis and predictive modeling tools.

“Extreme results often signal temporary anomalies, not lasting trends.”

Here’s how to recognize patterns:

- Look for repeated measurements. A single high or low result may just be noise. For example, students scoring 50% by guessing on a test likely regress to that average when retaking it6.

- Check sample sizes. Only 44% of medical studies replicate consistently6. Small datasets often exaggerate effects.

- Compare trends over time. If a basketball player scores 50 points one game but 20 the next, that’s likely regression, not skill loss6.

When analyzing performance, avoid snap judgments. Take the homeopathy study where patients’ scores rose from 44.3 to 49.4—but this barely reached the population average of 50.27.

Tools like predictive modeling help spot if changes are real or statistical quirks.

Ask yourself:

- Is the data based on enough observations?

- Does the change align with historical averages?

Remember: Regression to the mean isn’t just theory. It’s a lens to see through misleading extremes. Learn more about its foundations here.

Implications for Decision Making

“Understanding mental models like regression to the mean builds better decision-making frameworks.”

Using this concept can prevent costly errors. As mental models explain, it influences choices in many areas of life. Here’s how to apply it wisely:

In Personal Finance

Choosing funds based on recent gains is risky. Over 80% of top funds drop in rankings within five years due to regression to the mean8. Past success rarely predicts future results, as probability theory shows.

Instead, focus on long-term trends, not fleeting gains.

- Aim for diversified portfolios to reduce risk

- Avoid emotional reactions to short-term market swings

In Health and Fitness

Medical outcomes often change. For example, 80% of women with osteoporosis saw bone density improve in their second year of treatment, even without changes8.

Before adding new treatments, track long-term data. Sudden improvements might reflect natural statistical adjustments, not intervention success.

In Education

School programs targeting low-performing students often show initial gains. Yet, overall district scores stayed flat despite these improvements9. Small sample sizes (e.g., one test) can mislead decisions, as probability theory shows10.

Use multiple measurements and randomized trials to separate real progress from chance fluctuations.

Remember: Extreme results often revert to averages. Use this knowledge to make choices based on facts—not luck.

Common Misconceptions

Understanding the statistical phenomenon of regression to the mean can save you from big mistakes. For instance, companies might think a “miracle” strategy is the key to success after a big win.

But, results often go back to normal later. Studies show that 36% of what seems like improvement in schools or sports is just natural ups and downs, not real change3.

Overestimating Predictive Power

Extreme results can seem important, but they’re often just random. For example, a class that scores 10% below average one year might jump to 50% the next. This isn’t because of new teaching methods, but because of regression to the mean3.

Investors also make the mistake of chasing stocks after a huge jump, only to see them drop back to average statistical analysis shows3.

Confusing Correlation with Causation

- Baseball stars who hit 50 home runs one year rarely do it again. This is regression, not a decline in skill. Yet, teams might say it’s because of new training, ignoring chance3.

- Doctors might give a pill to patients with extreme symptoms, and their recovery might just be natural. It’s not always the drug’s fault3.

Remember, extreme outcomes are often just luck, not lasting change. Use statistical analysis to find real patterns and avoid chasing false hopes3.

Applications in Everyday Life

Understanding regression to the mean can change how you make decisions every day. Let’s look at three areas where this principle really matters.

Understanding Investments

Investors often think market ups and downs are about skill. But, extreme gains or losses usually go back to the average over time. For example, the LA Dodgers won a lot before a 2017 Sports Illustrated cover, but then lost many games11.

This emphasizes how important it is to stay calm during downturns and not get too excited during peaks.

Parenting and Child Development

Children who do well early in school might have setbacks later, while those who start slow might get better. This is just natural regression to the mean12. A study found that overachievers might see their grades drop, while others might catch up over time12.

This means it’s better to celebrate progress, not just the highs. For example, a student’s sudden top grades might not last, but steady effort is more important than one test.

Workplace Performance Evaluations

Managers can make mistakes if they only reward a team’s one-time success or punish a slump. In Massachusetts, schools saw underperformers naturally improve, not just because of special programs11.

Engineering teams use this to check quality control, looking at data to avoid misreading random dips or spikes13.

By understanding these patterns, you can make better choices. Whether it’s balancing investments, guiding kids, or evaluating teams. It’s about seeing the bigger picture, not just the highs and lows.

Avoiding Pitfalls Related to Regression to the Mean

Understanding regression to the mean is key. It’s about spotting hidden biases and data patterns. When looking at performance changes, remember that extreme results often come from chance, not skill.

For example, football managers who win a lot might lose the next season because luck balances out5. Health programs might also get credit for improvements that actually follow natural trends14.

“The control group in the Camden Coalition trial also saw a 40% hospital visit reduction, proving regression to the mean, not intervention, drove results.”

- Use statistical inference to test assumptions before drawing conclusions

- Apply data science tools to detect when small datasets distort trends15

- Aim for at least 10 data points per variable to avoid unreliable models15

Be careful of confirmation bias when seeing success. Doctors might give too many antibiotics for infections that go away on their own5. Always check if the progress is real over time.

When looking at changes, ask if it’s a real shift or just regression. The U.S. healthcare system spends a lot on a small number of patients, but many interventions fail to address chance14.

Ask yourself: “Would results stay the same with more data?”

To avoid regression pitfalls, collect consistent data, don’t jump to conclusions with small samples, and check trends over time. Data science can reveal patterns hidden by short-term extremes15.

Conclusion and Takeaways

Learning about regression to the mean and statistics terminology helps you make better choices. It’s about understanding how these ideas affect our daily lives and future plans.

Regression to the mean shows us that extreme results often return to normal. For example, a big sales increase might go back down as the economy settles. This is because of how things like GDP and sales are connected16.

Success is a mix of skill and luck, as Kahneman’s formula shows: Success = skill + luck18. Whether it’s improving grades or managing money, focus on the journey, not just the end result. For instance, students might see a 5-point increase per study hour17.

But, don’t jump to conclusions when things seem to go down. This is just regression at work18.